Introduction

This post relates a cool thing I did while I was teaching at uni way back in 2015. It is part of my continuing effort to self host all my academic work rather than have it on Academia.edu, which is now becoming enshittified. Despite its .edu domain Academia.edu is not actually run by an educational institution. It is a private company which got its domain when .edu domains were not strictly restricted to educational institutions, and then managed to get it grandfathered once the rules were tightened1.

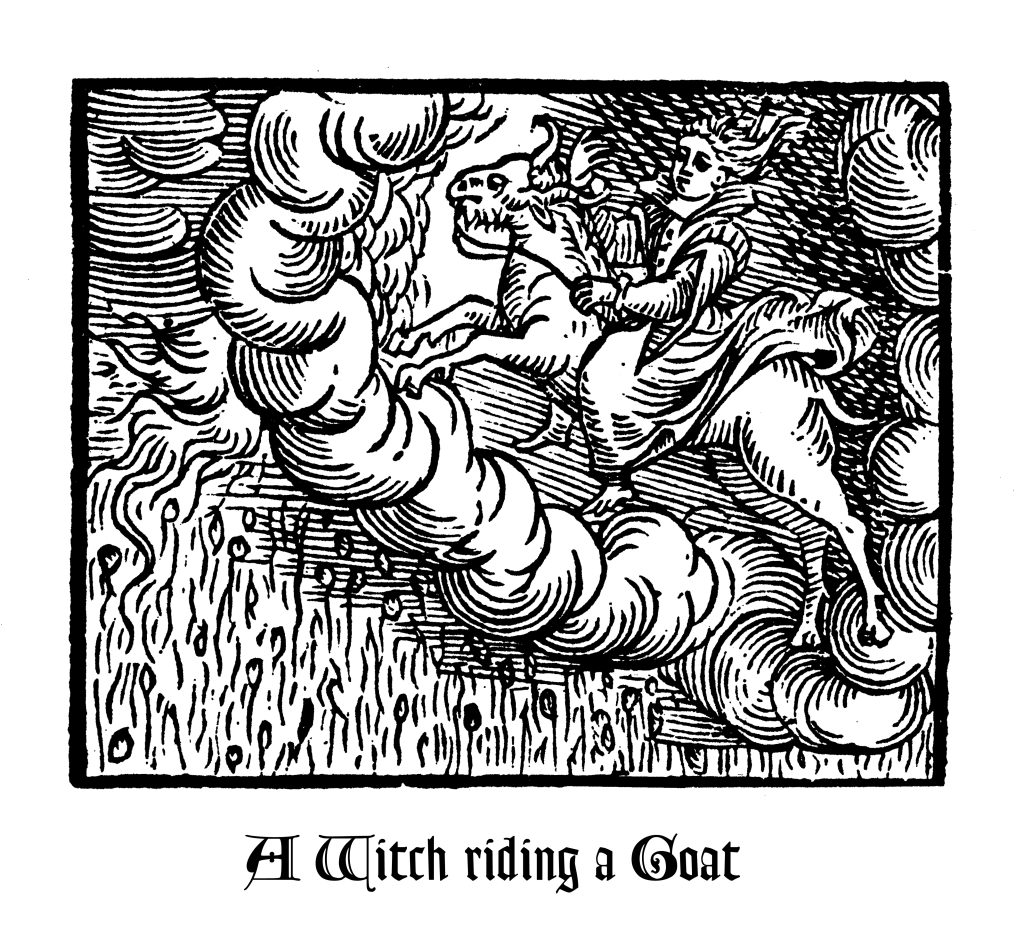

This teaching experience was the dawning of my realization that universities are not places where teaching is valued. But that’s a story for another day. It took the form of an immersive educational experience which undertook to role play a Pagan circle ritual in the virtual world Second Life as part of an undergraduate sociology unit at the University Of Tasmania (UTAS). I focus the discussion on the importance of fun as a vital component of learning while considering whether real educational value was achieved.

As educators expand into virtual worlds the importance of understanding the processes of digital domains increases. This leads to questions such as whether experiences in a virtual environment are authentic in themselves and whether there is real educational value in online interactive media, including games and shared virtual environments such as Second Life. An important aspect of education that is sadly often overlooked, especially at tertiary level, is fun. Csíkszentmihályi posited that people are most happy and attentive when in a state of flow2. From this we deduce that in order to achieve optimal educational value activities should induce flow.

Continue reading