Second Life is not a game, though it couldn’t have come to pass were it not for the computer games in which the basic functions and concepts it depends on were developed. This quick survey of the early history of computer games will show how these basic elements of functionality were present even from the earliest games. For a more detailed history of virtual worlds see Ok1.

Those who enter Second Life’s world are not known as players, but as residents. There are 37.3 million registered residents, of whom somewhere between 27 and 62 thousand (depending on the time of day) are in the world at any one time2. The figure for the number of total residents is however problematic. It would be more accurate to say that there are that number of registered accounts, as the number of residents does not equal the number of accounts. This is because any one human person can have more than one account. The number of accounts actually equals the number of avatars, as an account is tied to a single named avatar. If one wishes to have more than one avatar one must make a new account. Moreover not all avatars are for the use of a human, some are used for bots (short for robots) which are a method of automating an avatar by means of software.

Second Life is a world, a venue3. There has been a lot of debate about whether or not Second Life is a game4. However games have defining features that Second Life lacks. Most notable is the lack of victory conditions: there is no way to win, or lose, Second Life. The definition of what constitutes success is entirely up to the resident. Games have rules while Second Life has Terms of Service5 and community standards6. The free form nature of Second Life and the ability of users to create whatever they wish are important characteristics that set it apart from online games.

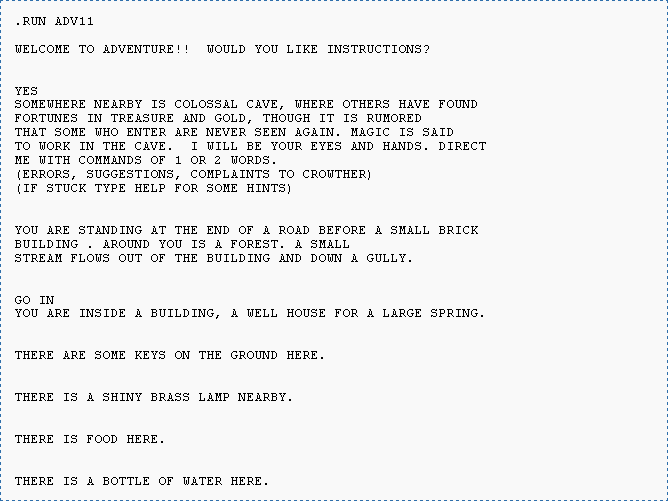

What is a virtual world? Looking first at the second of these two words, it seems certain to me that space is a defining feature of any world. The physical world we inhabit is defined for us by the fact that it has space. Worlds have space. But it can be imagined space. This space can be described in many ways. It could be the kind of imagined space found in early text based adventure games like Will Crowther’s Colossal Cave Adventure (see figure 17),also known as Adventure, written in 1975-19768, and which was the precursor for the entire genre of role playing adventure games9. Such games were incredibly successful for the first companies that exclusively made and sold computer games, like Adventure International, Scott Adam’s company that in 1978 released Adventureland for personal computers10. Unlike Colossal Cave Adventure, Adventureland included graphics as well as text (see figure 211).

Role playing adventure games were among the earliest computer games and initially their worlds were described by means of text only. The user would log into the game and see only text which described the world. These games allowed users to interact with the game using simple text commands like ‘look up’, ‘turn left’ and ‘get lamp’12. The game would then echo text to the screen that described what the user was seeing. Even in this earliest of games the functionality to pick up and carry objects was provided. This adds vital interactivity to the game and is practically ubiquitous in contemporary role playing and adventure games.

Though both Adventureland and Colossal Cave Adventure were single player games, the latter ran on a PDP-10 mainframe13, these games were the precursors of Multi User Dungeons (MUDs) – the first multiplayer real time virtual worlds. The first MUD was written in 1978 by an Essex University student, Roy Trubshaw14. In 1980 it became the first internet multiplayer online role playing game when Essex University connected its internal network to ARPANet15. Once MUDs had been developed game space was suddenly a shared space, and the rest is history. By 1992 there were more than 170 different multi user games on the net16. It is probably hard for those who have had multi user games and the internet for their entire lives to imagine, but there was something magical about the first time one connected to a network and communicated with other actual humans via it.

Such games have a virtual space, but rather than being presented on the screen in exquisitely rendered detail, as in Second Life, the spaces are imagined using the information the game developer provides – “It’s a virtual reality that exists in words”17. Though the space in such games was not graphically represented it is nonetheless a world in the same way that, say, Tolkien’s Middle Earth is a world. Its geography is described in detail and, once one becomes familiar with the world, one can wander freely in it. From this perspective text based MUDs are worlds even though we can’t see them. While text based worlds were incredibly popular when they first arrived on the gaming scene they were not durable. Once graphically rendered worlds arrived text based worlds virtually disappeared. They did however spawn the genre of interactive fiction, which still endures. Role playing adventure games have an appeal that shooter type games don’t. The actions of the user dictate the outcomes of the game to a much greater extent. No two players playing Adventure would have had the same experience because of the importance the player’s imagination has in creating the world of the game.

A common criticism of virtual worlds is that they are somehow not real, or are less real, than the meatspace world because they are simulated. Comparisons with the meatspace world are usually the basis for discussions of what is real or not. If things are in meatspace they are real things. By this logic alone virtual worlds are real, however there remains a common perception that they are not truly in this world. Ever since the earliest computer environments things in the virtual have been simulations of, or modeled on, things in the meatspace world. For example the cave system in Adventure was modeled after part of the Bedquilt Cave in Kentucky18, and modeled so well that a woman who had played the game and then went caving in Bedquilt Cave found she had no difficulty in navigating it19. This ability to simulate the real for educational purposes is one of the great advantages of virtual worlds.

Although it is tempting to venture down the rabbit hole and ask the question of whether the real world is simulated, there is simply not space here to examine that thread adequately. Instead I shall say that simulations are real things. Our modern world is full of simulations; synthetic fibres, artificial flavours, fiat money, things that seem like other things but aren’t quite them. Nonetheless these things are real. We know they are real because we can perceive them. I find myself in full agreement with Humphrey, who argues that perception is reality, that “to be conscious is essentially to have sensations: that is to have affect-laden mental representations of something happening here and now to me”20. All we know of the meatspace world we know through our senses. Our senses report to our brain which builds a mental model of the world inside itself. We call that model reality. Perception then comprises the nature of the real and whatever we can perceive is in some way real. Repetition of perceptions strengthens the reality status of things perceived. The things we perceive are perceptual clouds, our knowing of them built up from the serial perceptions we have of them. Not each perception of a given object is exactly the same, but they share enough similarity for us to group them together in a cloud of knowing and to thus identify them as being the same thing. Unless we gain omniscience we cannot know a thing as it objectively is, we can only know our perceptions of it. Our perceptions are therefore our reality. This space that we can perceive, or imagine we perceive, in text based worlds makes them virtual worlds. Once we have perceived things we remember, and repeat, and remix those perceptions and they become our new creations.

While the aforementioned text based worlds certainly have perceivable space this definition alone is not very useful when trying to talk about the online virtual worlds we have today. It is too broad. Bartle defines the world part of virtual worlds as “A world is an environment that its inhabitants regard as being self-contained. It doesn’t have to mean an entire planet: It’s used in the same sense as ‘the Roman world’ or ‘the world of high finance'”21. This definition focuses on the space alone, and while that is enough to make it a world, what is captivating about a virtual world for me is that I can interact with the space. Early on much of Second Life was just a dressed set, a backdrop against which one could set scenarios of one’s choice. Interaction was very limited indeed. While a world is still a world even if one can’t interact with it, it’s much more engaging if one can. Most of the early interaction in Second Life wasn’t very engaging, and was with other avatars, rather than with objects, as interactive objects were difficult to construct and often clumsy.

Castronova includes others to interact with in his definition when he describes virtual world as “crafted places inside computers that are designed to accommodate large numbers of people”22. Second Life is certainly crafted, but it is not a good exemplar of a space that accommodates large numbers of people. The maximum number of avatars one can have in a sim is 40, though in practice this number is lower, as sim performance is drastically effected as avatar numbers increase. Raph Koster, a virtual world developer, also sees the presence of others as vital and he includes the presence of avatars in his definition, “a virtual world is a spatially based depiction of a persistent virtual environment, which can be experienced by numerous participants at once, who are represented within the space by avatars23. While the presence of avatars makes it easier to relate to others, their absence doesn’t preclude the environment from being a virtual world, the world is still there. This definition, like Lortz’s, excludes not only single user worlds but also worlds where the user is not represented as an avatar but can still act in the world, such as worlds where the purpose of the world is its building rather than its habitation by avatars. It also excludes the worlds of literature.

Bell focuses on the synchronicity of the humans rather than the world in his definition, “A synchronous, persistent network of people, represented as avatars, facilitated by networked computers”24. Lastowka25 likewise sees the social aspects as vital, “Virtual wolds are persistent, interactive, simulated social spaces where users employ avatars”. Although I find Lastowka’s definition the most agreeable, like other definitions that exclude single user worlds, I find it somewhat problematic. I can run an instance of OpenSimulator, an open source virtual world server, on my desktop computer, not connected to the internet, and enter a virtual world where I am the only person who can enter it. Even though I am alone there, it is still a world, my world, and I can interact with it. Indeed I often do this because I am fascinated by building worlds and find building its own reward, never intending to share those spaces with others, nor even inhabiting them myself as an avatar. Having others around is nice, but it’s not a conclusive defining feature of a virtual world, while space and interactivity in that space are. Whether that interaction be imaginal or visual is not important. Whether it be solitary or communal is also not important. But what about avatars? Whether or not the user is graphically represented or not is not crucial. I consider text based worlds to be virtual worlds. Text based games have avatars too, although the player has to imagine them and describe them to others by means of text.

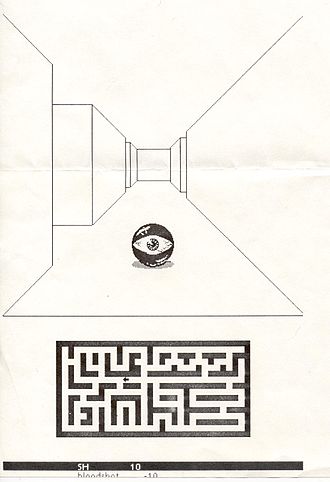

The first computer game to represent users as graphical avatars26 was Maze War, written in 197327. The players were represented as eyeballs (see figure 328).

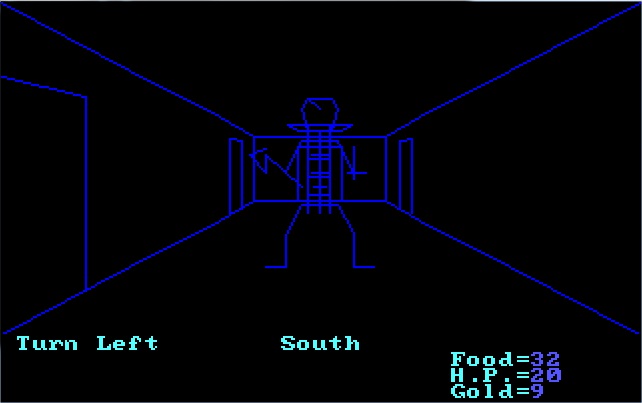

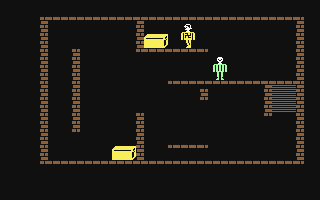

Akalabeth: World of Doom, one of the earliest examples of a role paying video game29 shows the player only as a cross in the top down view of the playing field, but introduced an important innovation, the first person perspective (see figure 430)31. Another approach taken by an early graphical game, Castle Wolfenstein (see figure 532), is to show the playing field and the player’s avatar, from a side view. However I prefer the first person view as it seems to me to provide a greater sense of immersion in the space.

While these two games have very basic avatars and functionality by today’s standards, they already contain all the basic features found in contemporary worlds; avatars, three dimensional representation of space, ability to collect and use objects and text entry. These basic functions form the core of contemporary worlds, which have extended and expanded them into more complex forms. For example, avatars are obviously much more complex and sophisticated in today’s games and virtual worlds than Maze War’s eyeballs, with most offering a huge array of customization of player avatars. The first customisable experience one encounters in Second Life is one’s avatar. Most avatars are humanoid, but this is not because non humanoid avatars are not possible, on the contrary, one’s avatar can be anything at all. I have seen toadstools, cardboard boxes, robots, dragons, clouds, giant eyeballs and many kinds of chimera, of which furries (human-animal hybrids) are the most prevalent. Most users create humanoid avatars of the same sex as their meatspace selves, though 72% have at some time created an avatar of the opposite sex33.

I have argued that neither avatars nor the presence of others are essential, and moreover that being connected to a network is also not vital, and indeed that text based games, which don’t even necessarily require a computer to create a world – for example Dungeons and Dragons, are still virtual worlds. Consequently I offer a definition of virtual worlds as persistent simulated or imaginal spaces that facilitate user interaction with that space. I feel this definition encompass all possible virtual worlds; the worlds of literature, text based games, MUDs of all kinds, graphical worlds and fully immersive three dimensional worlds like Second Life. If one wishes to stipulate, qualifiers can be added. Thus Second Life is a persistent, simulated, multi user, graphical online world where residents interact by means of avatars.

- Ok, A., (2011), Timeline of Virtual Worlds, https://annieok.com/timeline-of-virtual-worlds (original citation URL – now 404 – http://www.dipity.com/xantherus/Virtual_Worlds/, Accessed 02/04/2014) ↩︎

- Voyager, D., (2014), SL Metrics, https://danielvoyager.wordpress.com/2014/07/02/second-life-statistics-2014-summer-update/ (original citation URL – now 404 – http://danielvoyager.wordpress.com/sl-metrics/, Accessed 02/04/2014) ↩︎

- Castronova, E., (2007), Exodus to the Virtual World: How Online Fun is Changing Reality, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp. 59-60. ↩︎

- Boellstorff, T., (2008), Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human, Princeton University Press, Princeton, p. 22. ↩︎

- Linden Lab, Linden Lab Terms of Service, http://lindenlab.com/tos, Accessed 31/01/2014. ↩︎

- Linden Lab, Second Life Community Standards, http://secondlife.com/corporate/cs.php, Accessed 14/06/2009. ↩︎

- From http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ADVENT_–_Will_Crowther%27s_original_version.png ↩︎

- Jerz, D. G., (2007), “Somewhere Nearby is Colossal Cave: Examining Will Crowther’s Original ‘Adventure’ in Code and in Kentucky”, Digital Humanities Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 2, http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/001/2/000009/000009.html, Accessed 31/01/2013. ↩︎

- Somewhere Nearby is Colossal Cave: Examining Will Crowther’s Original “Adventure” in Code and in Kentucky http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/001/2/000009/000009.html ↩︎

- TRS-80, Apple II series, Atari 8-bit, TI-99/4A, Commodore PET, Commodore 64, IBM-PC, Commodore VIC-20, ZX Spectrum, BBC Micro, Acorn Electron, Dragon 32/64, Exidy Sorcerer. ↩︎

- From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Adventureland_Cover.png ↩︎

- Scott, J., (2010), Get Lamp, http://www.getlamp.com/, Accessed 11/02/2014. ↩︎

- Jerz, D. G., (2007), “Somewhere Nearby is Colossal Cave: Examining Will Crowther’s Original ‘Adventure’ in Code and in Kentucky”, Digital Humanities Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 2, http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/001/2/000009/000009.html, Accessed 31/01/2013. ↩︎

- Bartle, R. A., (1990), Early MUD History, http://www.mud.co.uk/richard/mudhist.htm, Accessed 31/01/2014. ↩︎

- Mulligan, J., Patrovsky, B., (2003), Developing Online Games: An Insider’s Guide, New Riders Publishing, USA, p. 444. ↩︎

- Rheingold, H., (2000), The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier, The MIT Press, Cambridge, p. 149. ↩︎

- Scott, J., (2010), Get Lamp, http://www.getlamp.com/, Accessed 11/02/2014. ↩︎

- Montfort, N. (2003), Twisty Little Passages: An Approach To Interactive Fiction, The MIT Press, Cambridge. ↩︎

- Adams, R., The real ‘Colossal Cave‘, http://www.rickadams.org/adventure/b_cave.html, Accessed 31/01/2014. ↩︎

- Humphrey, N., (1992), A History of the Mind: Evolution and the Birth of Consciousness, Simon & Schuster, New York, p. 155. ↩︎

- Bartle, R. A., (2004), Designing Virtual Worlds, New Riders Publishers, Berkeley. ↩︎

- Castronova, E., (2006), Synthetic Worlds: The Business and Culture of Online Games, University Of Chicago Press, Chicago. ↩︎

- Combs, N., (2004), A virtual world by any other name?, http://terranova.blogs.com/terra_nova/2004/06/a_virtual_world.html, Accessed 31/01/2014. ↩︎

- Bell, M. W., (2008), “Toward a Definition of ‘Virtual Worlds'”, Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, Vol. 1, No. 1, p. 2. ↩︎

- Lastowka, G., (2010), Virtual Justice, Yale University Press, New Haven, p. 31. ↩︎

- Maze War, Wikipedia ↩︎

- Damer, B. F., (1997), Avatars! Exploring and Building Virtual Worlds on the Internet, Peach Pit Press, Berkeley. ↩︎

- From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Maze_war.jpg ↩︎

- Barton, M., (2009), Dungeons and Desktops: The History of Computer Role-playing Games, A. K. Peters Ltd, Wellesley, p. 1. ↩︎

- From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Akalabeth.jpg ↩︎

- Scorpia, (1991), “C*R*P*G*S: Computer Role-Playing Game Survey”, Computer Gaming World, No. 87, p. 108. ↩︎

- From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:CastleWolfensteinC64.png ↩︎

- Bell, M. W., Castronova, E., Wagner, G. G., (2009), Surveying the Virtual World: A Large Scale Survey in Second Life Using the Virtual Data Collection Interface (VDCI), http://ssrn.com/abstract=1418562, Accessed 01/02/2011. ↩︎