Humans love anthropomorphisms! It makes it easy for us to think about concepts if we dress them up as humans. Death is no exception. Western culture has the grim reaper with his long black robe, scythe and his pale horse. But where did this Death come from and what came before him?

What is possibly the earliest known representation of Death, found at the Neolithic settlement at Catal Huyuk in Anatolia, shows Death as gigantic black birds, of vulture like appearance, who menace headless human corpses1. But this culture is mostly unknown to us so an understanding of this representation is beyond us at present. But they are black, which is the first attribute of our Death.

In Mesopotamian times the personification of Death was Nergal. In early lore he was handed charge of the underworld by his parents Enlil and Ninlil2, but it later times he was said to have obtained his dominion by marring Ereshkigal, Queen of the Great Below3. He is the first known representation of Death wearing a black robe, and he is armed with a scimitar and a staff4. Nergal is not a punishing Death but he is an inflicted death, which is reflected in his also being the god of war and pestilence. He is the essence of destruction, but there is no intent, no sense of death as a moral consequence, though deaths are sometimes brought about by him by means of daemons.

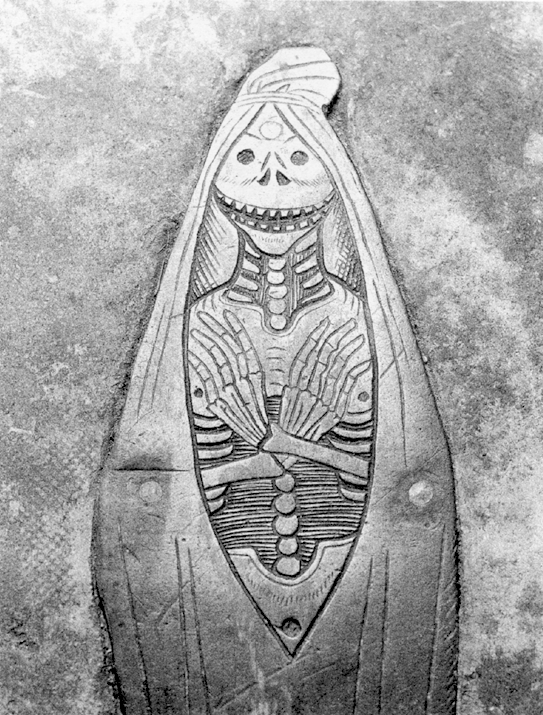

Alike to our Death, the winged motif is seen in the Roman personification of death, Mors, who is black winged. Mors is pale and emaciated in the extreme, and hovers over souls waiting for the moment of death. While it is possible that the Grim Reaper’s robe metamorphosized from these representations of wings I think it more likely that the robe derives from the medieval European practise of depicting the dead as skeletons, or bodies, wrapped in their shrouds (see below Norfolk 14995).

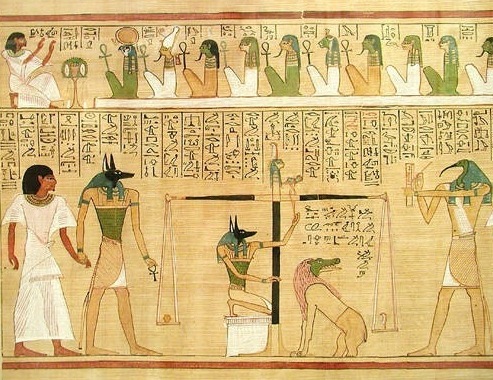

In Egypt, the god Anubis, though originally considered a protector of graves, came to be a facilitator of the journey between the physically manifest world and the afterlife, the first psychopomp, an attribute our Death shares. Long before Osiris, Anubis was the most important funeral deity. His epithet Foremost Of The Westerners relates to the fact that the Egyptians’ dead were known as the westerners because they were buried on the west side of the Nile and the sinking sun is believed to lead to the underworld in Egyptian religion. While Anubis is black, in this case the colour symbolises both the colour of the corpse after embalming, another of his responsibilities, and the fertility of the black soil of Egypt6.

The Greek personification of Death, Thanatos, is one of the sons of Night, both of whom are winged. Alike in nature to his brother Hypnos (sleep), Thanatos takes souls to death as if slipping into a great sleep. His act of consecrating the dead by cutting a lock of their hair with his sword allows the journey of the dead to the underworld. This concept of intervention may have come to the Greeks from the Egyptian tradition of the weighing of the soul against a feather in order to secure one’s place in the afterlife, though in the Egyptian tradition the soul is not consecrated but rather judged. Thanatos was not an altogether pleasant Death though. In Alkestis, Euripides describes Thanatos as “Dark browed, winged and robed”7 and has Apollo say of him that he is “Hateful to mankind and loathed by the gods”8. Thanatos also first introduces the concept of Death as a minion. He cannot act on his own initiative. The fates decide the time for death, or the Olympians decree it. Thanatos is merely the herald of death.

This conception is carried on in the Islamic tradition with Azrael as the Angel of death, whose name literally translates as whom god helps. Azrael is advised by Allah when it is time to take a human life and only then acts9. In the Koran Azrael is described as black winged and fearsome and even the other angels are in awe of him. Azrael does not know the time of death. When the time comes Allah allows to drop from his throne a leaf inscribed with the person’s name10. Azrael then has forty days to separate the soul from the body. Azrael acquired his duties of acting in regards to human life and death when Allah set the four archangels (Jibril, Mikal, Israfil and Azrael) the task of collecting dust from the Earth from which to create Adam. Only Azrael succeeding in this task, and as a result became responsible for human deaths11. But it is only the souls of believers that go to the seventh heaven, after having been gently pulled from their bodies. The souls of unbelievers are ripped from their bodies and then cast back down to Earth and they never reach heaven12.

In the Christian tradition Death is likewise a gatherer of souls, sometimes said to be a representation of Adam whose sin was said to be the first cause of death in the world. This Death is replete with symbols of time. Some, like the scythe, a symbol of the cycle of the harvest, and newer ones like the hourglass which is an agent of a more linear concept of time. Death’s horse most probably derives from the “pale horse” of Revelations 6:8 and the book of Enoch in the Christian Bible. Mounted Deaths also appear in other cultures in the west, most notably the Valkyries, the Norse mounted horsewomen of death, and also Gwyn Ab Nuud, who leads the Cŵn Annwn, the hounds of the Welsh underworld Annwn, on the Wild Hunt as the “god of the hunt who gathers lost souls and escorts them to the land of the dead on a white horse”13.

By the sixteenth century the western Death was complete with all his accoutrements; skeletal body, black robe, hourglass, pale horse and scythe. This Death, this Grim Reaper, personifies western conceptions of Death most comprehensibly. At a time when society was rigidly structured Death was the great leveler. In the sixteenth century Marseilles tarot deck Death is shown reaping a field where lay heads both crowned and bare. The scythe is also a symbol of time and, along with the hourglass, represents the inevitability of death. This link with time is why Death is often used as a symbol for change, hence the Death card in the Tarot.

One of my favourite Deaths is the one featured in the first book of Piers Anthony’s Incarnations of Immortality series, On A Pale Horse14. In this book Anthony presents a modern manifestation of Death who is a Grim Reaper type of Death, western culture’s most persistent image of Death, and a powerful mythic symbol. This Death, while an immortal manifestation of death itself is also a person. Death is an office, passed onto a new incumbent from time to time. How? By killing the old death. The new incumbent in this instance is Zane, a no hoper who comes to the point of suicide but inadvertently botches it and kills Death, who had come to take his soul. It turns out that Zane can kill Death because he has killed the incumbent and not the office. The office is inviolate but the officeholder can be vulnerable, with the accoutrements of Death providing the invulnerability required for the exercise of the office. The Death Zane killed carelessly had his hood off his face, rendering him somewhat less invulnerable. Once the old Death is dead Zane assumes his role, dressing himself in the cloak, which provides invulnerability to the wearer and gives him the appearance of a skeleton while he wears it, and the shoes, which allow him to walk on anything; air, water, anything because Death must be able to go anywhere.

Like the Grim Reaper, this Death has a timepiece, in this case a watch which counts down to his next appointment with a dying soul. He also has a weapon, the traditional scythe, and a horse, well he’s usually a horse. Death’s horse, Mortis, is a most adaptable steed. When necessary he transforms himself into a pale limousine, or a plane, or a boat, or whatever vehicle is necessary for the fulfillment of Death’s rounds. But despite his technological toys this Death is still addressing the big questions; Why are we here? Why do we die? Where do we go then?

Once Zane assumes the role of Death he has to discover how to fulfill the office’s job requirements, and it is through his process of discovery that we get to explore the part of death in human experience. Immediately after the previous Death’s death Zane is visited by Fate, who provides some explanation of his new role for him. Death’s job is to attend personally only the demise of those whose souls are in near perfect balance. He must then judge the balance of the soul to determine whether it will proceed to heaven or to hell. In this he is merely an impartial workman, a reaper of souls who cares not wither souls go, he simply examines the evidence and then directs the soul to its destination. Well that’s the plan anyway… Zane soon stars to question not only where his client’s souls should go, but whether they should die in the first instance. He asks the question, why does God allow death? The answer is that God is having a bet with Satan. The deal is that souls will get sent to Earth for testing in a material manifestation. They will have free will and full disclosure as to the results of their choices. The good go to Heaven and the bad to Hell. Satan and God have promised not to interfere in the physical world. Satan, of course, breaks the deal all the time, while God upholds it perfectly. Consequently Satan has an active presence in the world, he has even engaged an advertising agency to promote Hell (Winter is cold, your life is shot; go to Hell where it’s really hot!) while God’s presence is felt only through human agents, i.e. priests etc.

The elements of this twentieth century story are the same basic elements symbolically rendered in the sixteenth century Death. Death is, in both representations, apart. Invisible except to his clients, immortal (unless he slips up), not an agent of either God or Satan, not of this world, nor of Heaven or Hell, incontestable in his own domain. In Anthony’s book Death’s apartness is illustrated by having him reside in purgatory. It is to this same place that he delivers the nearly perfectly balanced souls so that they may work out in which direction their subtle imbalance is. This representation has inherent in it a Christian geography of the universe, to wit, Earth, Heaven, Hell, Purgatory. God and Satan vying for souls and the world of the physically manifest as a testing ground for souls are certainly Christian themes, but Anthony also presents pre-Christian ideas. Fate, his visitor, is clearly the Greek Moirae, she manifests variously as Clotho, Lachesis or Atropos, and it is she who decides the time of each person’s death, even Death’s.

Death’s role in these stories, both classic and contemporary remains much the same. He is a glyph which contains the clues which start us thinking about our place in the universe. A symbol by which we can communicate our conceptions of the structure of the universe and of the human soul. He is a guide to the next world, but he is not taking bodies. He is an exposition of the idea that humans are comprised of both a physical body and a non manifest soul. His very existence indicates a belief in an afterlife, if he is collecting souls where is he taking them? Why is he taking them? What would happen if he stopped? Zane does go on strike, refusing to collect more souls to prevent a good woman from going to Hell untimely. Anthony uses the device of this twist of the story to examine an important moral question about Death, to wit, what if people want to die? Should they be allowed to hasten their own demise or will they pay an eternal price for doing so? While he is on strike Zane visits a nursing home. Because he is on strike the old folks cannot achieve the release of death. They argue with him, admitting the cause for his strike is fair, but speaking of the torment of living in misery or pain, living lives that are completed and possessing souls tired of the world and seeking only release, but living only because they fear a divine punishment should they choose suicide.

Alike with Deaths of previous times Zane as Death’s role is as a liberator of souls. But are all souls liberated alikewise? Do they all go willingly and easily? Exploring a theme common by the eighteenth century in western culture15 i.e. that the good soul goes easily into death while the evil soul has a bad death, Zane ponders on the nature of the separation of the soul from the body. What does he have to do? Just pull it out, or is more dynamic action required? This conception appears first in Islamic culture where the Koran mentions (79: 1 & 2) the souls of the good being drawn out gently and the souls of the wicked being wrenched out violently. Zane encounters an evil old man whose soul he has to wrestle out using his scythe, a most unpleasant experience for the man and Zane alike.

Zane as Death is a personification performing a role which allows us to evaluate death. A device created by human perceptions of death in order to give the ideas a shape that we may more easily consider them. Perhaps all representations of gods are this, models which give principles shape that the mind may encounter them. Death is the oldest companion of humankind, so it is unsurprising that his form is as well developed as any god. Alike to the form of the dead but unlike them in his animation. Holding the symbols of time, and hence change, he is a powerful figure for the imagination to create and then consider.

Humans’ first considerations on the possibility of a non material existence may well have been as a result of pondering death. Surely the first thing that would occur to you on the death of another would be, where did they go? The body remains, but its vital force is gone. Of course, it could be that it is only that we are in such a state of disconnect with the universe in the present age that we can conceive of this as a question. A more connected age surely knew the answer exactly. Death denial is a huge feature of our culture. We seldom, if ever, see dead people. We pretend to our children that death isn’t a thing. We do our best to hide death on all occasions. Our fucked up relationship with sex and this hang up about death are the two biggest pathologies of our culture.

The Death we have inherited from our ancestors is a figure of fear and dread, a manifestation of what is perhaps our greatest fear, the fear of the inevitable unknown. If we all came to our rest absolutely assured that we would be spending eternity in a heavenly paradise, or that we would be reborn again in this world, Death would hold no fear. This of course is one of the uses of religion. That personifications of Death through human history are overwhelmingly negative and fearful is a strong indicator of the trepidation and fear with which humans approach the eternal. Our ancestors it seems had just as many doubts about eternity as we do today. And they dressed these doubts and fears as Death; skeletal, armed, ghastly, and absolutely inevitable.

Of course my very favourite Death is Pratchett’s, but that’s a story for another time.

- Leilah Wendal, Encounters With Death, New Orleans, Westgate, 1996, p44. ↩︎

- Zolyomi, Gabor, Hymns to Ninisina and Nergal on the tablets Ash 1911.235 AND NI 9672 in Your Praise Is Sweet, British Institute for the Study of Iraq, 2001, p 419. ↩︎

- Gadotti, Alhena, Never Truly Hers: Ereškigal’s Dowry and the

Rulership of the Netherworld, Journal Of Ancient Near Eastern Religions, Brill, no. 20, 2020, pp 1-16. ↩︎ - Nergal ↩︎

- Steven Bassett (Ed.), Death in Towns, Leicester University Press, Leicester 1992, p202. ↩︎

- Wilkinson, R. H., The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, Thames and Hudson, New York., 2003, p189. ↩︎

- Robert Garland, The Greek way of death, London, Gerald Duckworth & Co. 1985, p58. ↩︎

- Robert Garland, The Greek way of death, London, Gerald Duckworth & Co. 1985, p58. ↩︎

- Smith, J. I., & Haddad, Y., Islamic Understanding of Death and Resurrection, State University of New York Press, p. 35. ↩︎

- Houtsma, M. T., E.J. Brill’s First Encyclopaedia of Islam, Brill, 1987, p. 570. ↩︎

- Ibn Kathir, Stories of the Prophets Complete History of the Life of the Prophets from Prophet Adam to Prophet Isa, Qisthi Press, 2017, p. 46. ↩︎

- Hadith on Death ↩︎

- Leilah Wendal, Encounters With Death, New Orleans, Westgate, 1996, p26. ↩︎

- Piers Anthony, On A Pale Horse, 1985, Panther, London. ↩︎

- Nigel Llewellyn, The Art Of Death, 1991, Reaktion Books, London p 36. ↩︎