Violet Mary Firth, later known as Dion Fortune, was a strange child, reputedly psychic all her life, who grew into one of the most formidable occultists of her day. Her work was an important influence on many Neo Pagans, most notably Gerald Gardener, but also on others later such as Druids Isaac Bonewits and John Michael Greer. She was an interesting mix of clairvoyant medium and university trained psychologist and much of her work was remarkably shamanistic in character.

Born in Llandudno, North Wales, on the 6th of December, 1890, her parents converted to Christian Science when she was fourteen. One can see the influence of this early exposure to Christian Science in all her work. Christian Science does not view Jesus as simply a moral exemplar, rather his healing works, as well as his own victory over death and the grave, are regarded as demonstrating that all the ills and limitations of the mortal state can be overcome, in proportion, as one gains the mind of Christ, i.e. an understanding of one’s true spiritual status. This requires a penetration beyond material appearances into a spiritual order of being, one that traditional Christian orthodoxy associates with a heaven in the hereafter, but that Christian Science considers to be scientifically demonstrable in human life. This theme of recognising the oneness of the magical and the physical would echo through Fortune’s work for all her life. The melding which she sought is remarkably similar to an underlying principle of shamanism, i.e. that the spiritual has a real and demonstrable effect on daily life, especially in use for healing. Many of the practices which she, and her community, undertook are equivalent to those discussed by Vitebsky1 in his overview of shamanism. Most notably, she was not only a solo practitioner but the centre of a community, on whose behalf she acted.

Vitebsky characterises shamanism more as a set of practices and experiences than as a body of beliefs. These include, but are not limited to; soul flight, trance, mystic visions, gaining spiritual and physical powers and knowledge of the pharmacology of the plant kingdom. Vitebsky feels strongly that soul flight is the defining characteristic of shamanism as a whole but I feel this is an oversimplification. All the features of shamanic practise coalesce equally into a coherent whole.

Even among shamans who spend some considerable part of their time alone the focus of their activities is to improve the lot of the community whom they represent and to act as a mediator for that community. There does not seem to be such a thing as a wholly solitary shamanic practitioner. Indeed Vitebsky stresses the importance of the shaman’s role as a mediator or intercessor for the community, and the vital social function the shaman undertakes of restoring harmony to the community after some upset or perceived upset. Dion Fortune filled this role in her community.

Vitebsky describes how the shaman’s help is often sought by the community when the hunt fails. In modern societies we are no longer dependent on a successful hunt in order to survive, however we may still look to spiritual modes of assistance when the necessities of daily life are not forthcoming or in times of personal distress. This seeking after wellbeing is of course found in many religions, the extreme form of this being the perversion of Christian doctrine that is the prosperity gospel.

Whereas some writers2 3 have discussed the gods of people practising shamanistic forms of religion Vitebsky never even mentions them. Having read his book one is none the wiser as to if shamanistic forms of religion have a concept of a god or gods at all. But that is because shamanism is not a religion, but rather a set of practices found embedded in many religions. Indeed Eliade reveals this in the subtitle of his book Shamanism: archaic techniques of ecstasy, wherein he points out that shamanism most frequently coexists with other systems4. However Vitebsky asserts that shamanistic religions have been persecuted and marginalised by the growth of centralised religions. These apparently contradictory claims can in fact both be true. Shamanism may be quite happy to coexist with other systems but they may not be happy to coexist with shamanism.

Vitebsky also addresses the importance of animism in shamanism. He mentions how the shamanic journey has as its basic purpose the understanding of spirits and the true nature of things and, most importantly, that this understanding is sought in order to be able to effect change. He mentions that the shaman’s journey may encompass not only the landscape of the physically manifest world but also the landscapes of the unmanifest. And he emphasizes how shamanism considers humans to not be separate from the divine, but rather surrounded by the divine and partaking in divinity as a regular occurrence, most commonly through shared mystical experience.

Following this he outlines the selection of shamans, mentioning how most often it is not a chosen vocation but imposed by the spirits and how shamanism is often inherited. He stresses the importance of the process of transformation and rebirth that begins a shaman’s career and notes that shamans may be sexually ambiguous as a part of or as a consequence of this rebirth.

Finally he considers the possibility of a shamanic revival in the Western world. He essentially dismisses the validity of modern, Western shamanic practitioners. Primarily it seems he feels the social embeddedness of tribal shamans is missing in the modern, western setting and that without this embeddedness any modern tradition does not represent a genuine form of shamanism. Contrariwise I contend that Dion Fortune is an example of such.

Because shamanism is not a religion but rather a set of techniques used within various religions we need to expand our view of who is practising shamanism. Trying to assert that only practitioners of certain indigenous religions are shamans is a holdover from colonial theories of the evolution of religious forms that usually places practices such as shamanism near the bottom, and labels them superstitious, and puts Christian practices at the top of an imagined hierarchy and labels them religious.

“I was supposed to have died as a baby. I was declared dead and lay dead for many hours in my mother’s lap, for she could not be persuaded to put me down, and at dawn I revived but the eyes that looked at my mother, she told me many years afterward when I asked her the cause of my strangeness, were not the eyes of a child, and she knew with the unerring instinct of a mother that I was not the same one.”5

This is Fortune’s own description of the circumstances of her birth and it demonstrates the first of many ways in which her coming to be a magical practitioner is similar to the manner in which Vitebsky describes the nature of those chosen to be shamans. She was, from the very first, a peculiar child. All through her childhood she had visions and memories of previous lifetimes. Fortune was reputed to have had visions of Atlantis when she was four and later in her life she believed that she had been a temple priestess there. During puberty, she says, she developed mediumistic abilities.

In her adolescence she suffered what she termed a psychic attack, which left her with nervous exhaustion. She set about finding a cure for herself and, after studying psychology at the University of London for a while, she came to realise that her problems were of a spiritual nature. The influence of Christian Science on her thought is revealed here. Her strange illness correlates with much literature regarding shamanism to the effect that those who become shamans often have suffered from unusual illnesses which they learn to control only by becoming shamans.6

While still young Fortune had several encounters which demonstrated her psychism, but she passed them off as chance. But one day she had a dream that would set her on the road to her magical career. She describes a vision7 in which she is taken on a journey to the Himalayas and there meets with two powerful spirit beings, one the master Jesus and the other the master Rakoczi8. This exemplifies the concept expressed in shamanism as the ascent of the cosmic mountain that the shaman must take at the time of their initiation in order to contact spirit beings9. Once these masters had revealed themselves to her they let her know that she had been accepted as a pupil by one of them and that she needed further instruction in order to complete her training. This experience has significant commonalities with the various shamans mentioned in Vitebsky’s piece. To wit, she spiritually traveled to another place, met with spiritual beings there, was accepted as a pupil of the spirit master and was told she must expect further training. This twin training, both experiential and pedagogic is another feature of shamanistic religions.

When Fortune was just twenty an event occurred which would shape the future course of her life. She was working in an educational establishment under a woman who, she says, had traveled in India extensively and who Fortune felt had substantial psychic powers. She describes vividly, in Psychic Self Defence10, how she came to grief after an encounter with this woman. She relates how she had been trying to assist an old lady resident in the establishment who had fallen prey to the proprietress. This unfortunate old lady was apparently in possession of an income which the proprietress desired to obtain control of. Fortune says she had seen the proprietress take unjust actions against others previously and that she wished to protect the old lady from such action. So she packed the old lady up and sent her back to her family while the proprietress was away for the day. Upon her return the proprietress took violent exception to Fortune’s actions and proceeded to use, what modern psychology would call hypnotic suggestion, in order to convince Fortune of her incompetence in the matter. Fortune resisted but found herself “drained of all my vitality”11, a condition which she says persisted for some three years and was only fully resolved once she was initiated into the Alpha and Omega lodge, a first generation descendant of the Golden Dawn. It was this critical experience of psychic attack that induced her to study analytical psychology, to join the Theosophical Society (though she later left due to a dissatisfaction with their ideas) and devote herself to occultism. Kenneth Grant describes this period of her life in his book The Magical Revival thus;

“She was initially strongly influenced by the doctrines of Aveling, but her interest in these gradually waned and she became absorbed with the theories of Freud, Jung, and Adler. While studying these, Fortune noticed the close connection between certain psychosomatic states and those described by ritualists of the Eastern Tantras and the Western Qabalistic traditions. ”12

Fortune decided to seek out an experienced mystic who she had encountered earlier in her life in order to receive training. He was the Irish occultist and Freemason Dr. Theodore Moriarty who had developed an anthropological interest in the Bushmen of South Africa, where he had gone to recuperate after contracting tuberculosis.

Fortune attended courses in psychology and psychoanalysis at the university of London, and became a lay psychotherapist in 1918 at the East London Clinic, which was where she met and worked with Moriarty. Moriarty also operated a magical lodge in Hammersmith, and in 1919 Fortune was listed as an acolyte in this order. She went on to work for some years at his nursing home as a psychotherapist.

Another incident in her life reveals one of her key ideals which she has in common with the shamanistic practitioners discussed by Vitebsky, that of devoting one’s life to helping a particular group. In 1920 she became involved with B.P. Wadia, an Indian mystic visiting England at the time. She participated in his group for a time but ultimately left as she felt that her spiritual calling was to help the group soul of the British people. She did not believe that Wadia was capable of helping the British people because of his being an Indian and using Indian methods. In this she agreed with Jung that Western methods were the most suitable for Western people. Perhaps she was moved to articulate this as a reaction to the split between the followers of the Eastern and Western traditions in the west, which came about as a result of the collapse of Madam Blavatsky’s Theosophical society, Fortune being heir to those who had opposed Blavatsky’s militant anti-Christian views i.e. The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor and thence the Golden Dawn13. Fortune explains her rationale well in Sane Occultism;

“The pagan faiths of the West developed the nature contacts. Modern Western occultism, rising from this basis, seems to be taking for its field the little-known powers of the mind. The Eastern tradition has a very highly developed metaphysics…. Nevertheless, when it comes to the practical application of those principles and especially the processes of occult training and initiation, it is best for a man to follow the line of his own racial evolution…. The reason for the inadvisability of an alien initiation does not lie in racial antagonism, nor in any failure to appreciate the beauty and profundity of the Eastern systems, but for the same reason that Eastern methods of agriculture are inapplicable to the West – because conditions are different”.14

It was in an effort to remove the influence of Wadia that she actively sought the assistance of the spirit teachers she had met in her earlier vision. In order to contact them she utilised certain magical signs and rituals she had been taught by Dr. Moriarty. Upon doing this she felt the foreign influence had been banished and received a message to seek out further instructions. She asked for a sign and was delivered one. This being proved she felt she had no choice but to follow the spirit helper’s teachings.

She had tried to establish herself as a psychotherapist but patients with strange spiritual illnesses seemed to follow her. She tried to pass them on to other experienced occultists whom she knew, but they just kept on arriving on her doorstep. She wrote the book The Secrets of Dr Taverner15, which contains stories of spiritual and physical problems which were cured by spiritual methods. This book was published as fiction, however she says in Psychic Self Defence16 that all of the stories are based on events which she encountered while working for Dr. Moriarty at his nursing home.

It was only after a long period of time in which she was repeatedly presented with physical illnesses needing psychic cures that she chose to give up her career as a psychotherapist and devote herself to the mystic. This reluctance to commit to the spiritual is another commonality with Vitebsky’s writings. He says that shamans are often reluctant to accept their calling and must be continually persuaded to do so.

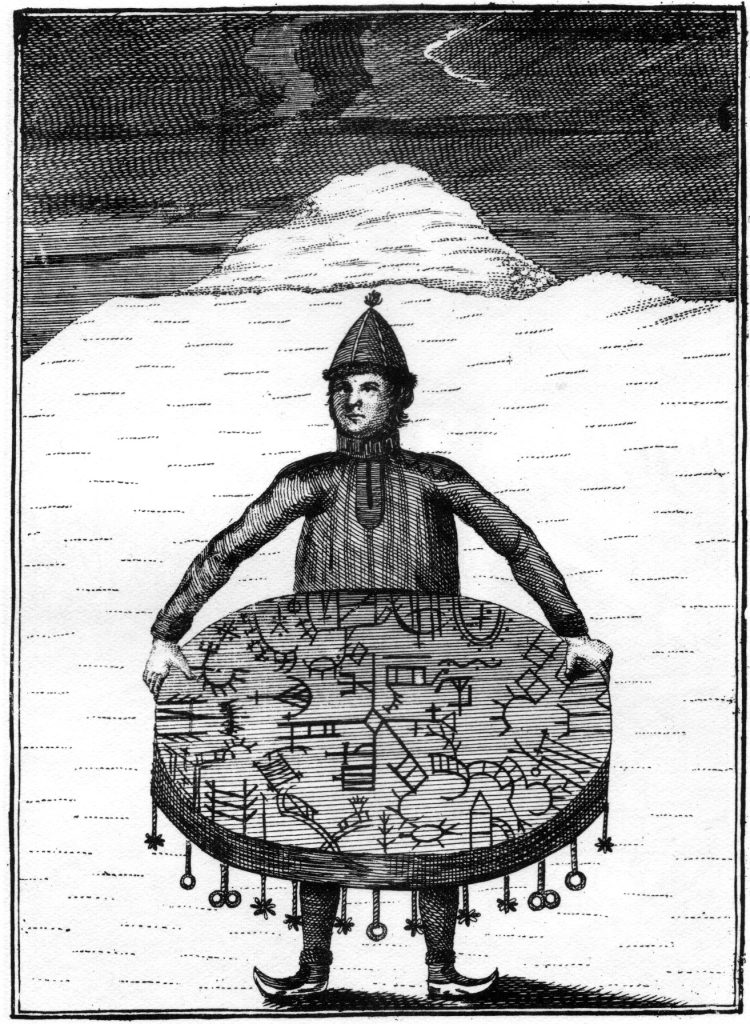

Fortune was initiated into the Alpha and Omega, at which time she reported that she felt her psychic leak had been healed17. This enabled her to recover from her nervous exhaustion, at which time she felt a renewed sense of purpose in her magical work, subsequent to which she took the name Dion Fortune. Similarly to in shamanism, names of power have an important place in qabalistic magic. Like shamans, qabalistic initiates take a magical name as part of their initiation and names are important components of magical rituals used to gain access to special powers in both systems. In both qabalistic magic and shamanism the adoption of a new identity after initiation marks a new beginning for the practitioner, whether it is by the taking of a new name, adopting sexually ambiguous clothing or wearing a particular costume which sets them apart18.

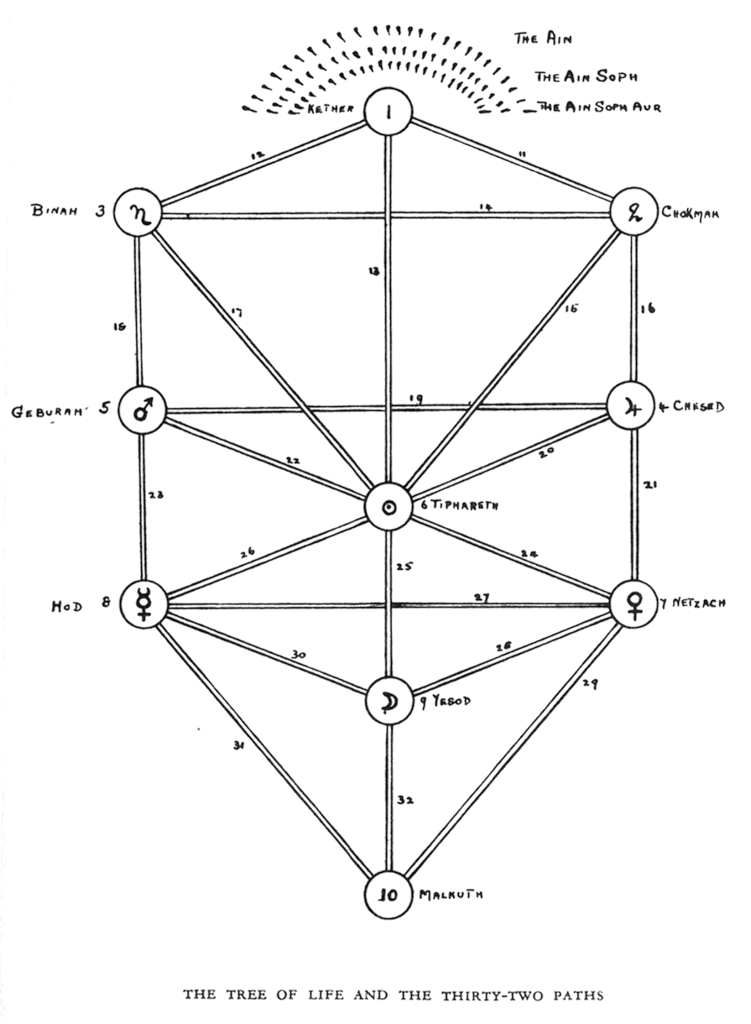

Fortune studied Hermetic Qabalah, which is a descendant of Jewish Kabbalah, via Christian Cabbalah. In Hermetic Qabalah the structure of the universe has many similarities with the view of the universe held by many shamanistic religions. There are many layers and each is inhabited by its own particular spirit beings. The qabalistic universe is made up of many spheres called sephirot19. Likewise shamanistic conceptions of the shape of reality describe a number of spheres20.

Alike in Hermetic Qabalah and shamanism each sphere represents a state of being or awareness and is controlled by spiritual powers who are represented as gods, objects, colours, sounds or animals. The role of a practitioner is to travel up the tree on which these spheres rest, making contact with the helper spirits associated with each level and to eventually reach the highest point of the tree, where the godhead exists. In order to traverse the path of the tree many rituals are undertaken, including meditations, ritual magic and self induced trance. The mastery of each of these spheres, or the contacting of the spirit being which resides in each, requires a particular spiritual journey to be made. The process of undertaking these journeys is the vocation of the initiate.

In qabalah these spheres are laid out on The Tree Of Life in a particular pattern. The sephirot are connected by 22 paths, but each sephirah is also considered a path, the traveling of each of these paths indicates a particular spiritual journey taken and lesson learned. Many shamanic traditions likewise use the motif of the Cosmic Tree on which shamans must climb in search of gnosis and which Eliade says “is to be regarded as one variation of the mythico-ritual theme of ascent to heaven”21

In shamanism cosmic trees are likewise described as having various levels which are marked by a variety of different signifiers; coloured ribbons23, a particular number of branches24, nests containing the creator’s children.25 These trees stand at the centre of the world and form its spine, which is alike to the qabalistic anthropomorphic representation of the Tree Of Life, in which the middle pillar is associated with the human spine26.

By 1924 Fortune had built a strong community around herself. The group lived in a house at the base of Glastonbury Tor and pursued the goal of spiritual healing. By this time Fortune had established regular trance contact with her spirit guide known as Lord Erskine, with whom she made regular contact and from whom she sought advice and information on how to effect her goal of working for the betterment of the British people. The obtaining of a spirit guide is likewise a vital part of becoming a shaman27.

On behalf of her community Fortune often went into trance in order to seek the answers to problems being experienced either by individual members of the community or by the community as a whole. Fortune was a special member of her community as she had mediumistic skills and inner plane contacts which were not accessible to everyone in the group. Just like a tribal shaman she was the conduit through which her group accessed these powers.

Apart from this more generalised effort at spiritual healing the group regularly sought Fortune’s assistance with individual physical problems. Usually Fortune would enter into trance and find that the sickness was the result of some unresolved situation or that it was caused by the activities of either beings on the spiritual planes or by the efforts of other occult practitioners against the sick person.This is exactly the method employed by shamans.

Attacks from other magical practitioners are also a feature of shamanism. For example, Carlos Casteneda describes enduring a series of spiritual attacks in The Second Ring Of Power28, Eliade29 cites Lehtisalo’s30 mention of shamanic attacks wherein shamans try to destroy the souls of other shamans, and Fortune herself reported that she was the subject of occult attacks by other occultists. Most famously with Moina MacGregor Mathers, the widow of the renowned occultist Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers, one of the founders of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

“The events, as outlined in “Psychic Self Defence”, began with a general sense of unease and restlessness, with bursts of uncontrolled psychism, that led to a definite sense of menace and antagonism and picture images of demon faces. There followed a virtual plague of cats upon the physical level, associated with astral simulacra of large felines, which were eventually despatched by normal occult banishing formulae. Then, at the Vernal Equinox, when Fortune moved out into astral consciousness she saw her adversary, in the full robes of her grade, barring her entry, and forbidding her to make use of the astral pathways. Fortune refused to recognise her authority in this respect and appealed to the Masters. A battle of wills followed in which she got the worst of it. She had the sensation of being whirled through the air and falling from a great height, to find herself back in her body, not where she had left it, but in a heap in a far comer of a room which was in considerable disarray. By virtue of etheric repercussion her body had somersaulted round the room during the course of the inner struggle. Somewhat shaken by the experience she realised that if she accepted defeat now her occult career was finished, and in a subsequent attempt, again invoking the Masters, after a short sharp struggle she got through. The fight was over, and she never had any further trouble from this source.”31

Fortune continued to enter trance to contact Lord Erskine for most of the rest of her life, continually stating that her vocation was to work for the betterment of the British people and this is most clearly demonstrated by her endeavours during the period of the second world war. During the Battle of Britain, when it seemed possible that the Allies might lose the war, Fortune set upon an undertaking with a dual purpose. On the one hand she sought to rally the spiritual powers of British people in opposition to the Germans and on the other hand she sought to direct destructive spiritual powers against them, particularly against German occultists. This is clearly elaborated in her book The Magical Battle Of Britain32. Essentially she gathered together her group and they would perform rituals and seek the assistance of their spirit guides in order to effect the outcome of the war. Here is the best evidence that “She was becoming to her race what a shaman is to his tribe”33.

The constant visions and development of mediumistic abilities at an early age marked Fortune out for a shamanistic life. Also clearly shamanistic are her spiritual afflictions and her eventual reluctant decision to adopt spiritual means to cure them. Fortune’s practices clearly illustrate her role as a shaman. Her role as a spirit medium, much of which was focused on healing, both in her own group and in her work with Dr. Moriarty over many years is a classic shaman’s role. Taking on the role of supporting her entire nation with her actions during the Magical Battle Of Britain is taking her shamanistic care of her community to a whole new level.

- Vitebski, Piers, (2001), The Shaman, Duncan Baird Publishers. ↩︎

- Eliade, M., (1964), tr. Willard Trask, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, London, Arkana. ↩︎

- Bowie, Fiona, (2000), The Anthropology of Religion, Oxford, Blackwell. ↩︎

- Eliade, M., (1964), tr. Willard Trask, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, London, Arkana ↩︎

- Knight, Gareth, (2000), Dion Fortune and the Inner Light, London: Thoth, p 13. ↩︎

- Eliade, M., (1964), tr. Willard Trask, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, London, Arkana ↩︎

- Knight, Gareth, (2000), Dion Fortune and the Inner Light, London: Thoth, p 39. ↩︎

- Richardson, Alan, (1991), The Magical Life Of Dion Fortune: priestess of the 20th century, London, Aquarian, pp69-73. ↩︎

- Eliade, M., (1964), tr. Willard Trask, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, London, Arkana, p 269. ↩︎

- Fortune, Dion, (1930), Psychic Self Defence, London, p. 12-17 ↩︎

- Ibid p. 16 ↩︎

- Grant, Kenneth, (1973), The Magical Revival, New York, p. 175 ↩︎

- Godwin, Joscelyn, (1994), The Theosophical Enlightenment, Albany: State University of New York Press, p. 355-362 ↩︎

- Fortune, Dion, (1967), Sane Occultism, Denington Estate, Aquarian, p.161-162 ↩︎

- Fortune, Dion, (1962), The Secrets Of Dr. Taverner, Minnesota, Llewellyn. ↩︎

- Fortune, Dion, (1930), Psychic Self Defense, London, Aquarian, p 59. ↩︎

- Fortune, Dion, (1930), Psychic Self Defense, London, Aquarian, p 18. ↩︎

- Eliade, M., (1964), tr. Willard Trask, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, London, Arkana, pp 145-180 ↩︎

- Fortune, Dion, (1987), The Mystical Qabalah, Wellingborough, Aquarian, pp 62-71. ↩︎

- Eliade, M., (1964), tr. Willard Trask, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, London, Arkana, p 260. ↩︎

- Eliade, M., (1964), tr. Willard Trask, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, London, Arkana, p 121. ↩︎

- Fortune, Dion, (1987), The Mystical Qabalah, Wellingborough, Aquarian, p 325. ↩︎

- Eliade, M., (1964), tr. Willard Trask, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, London, Arkana, p 121. ↩︎

- Eliade, M., (1964), tr. Willard Trask, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, London, Arkana, p 285. ↩︎

- Eliade, M., (1964), tr. Willard Trask, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, London, Arkana, p 70. ↩︎

- Fortune, Dion, (1987), The Mystical Qabalah, Wellingborough, Aquarian, p 55. ↩︎

- Eliade, M., (1964), tr. Willard Trask, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, London, Arkana, p 107. ↩︎

- Casteneda, Carlos, (1977), The Second Ring of Power, Hamondsworth, Penguin. ↩︎

- Eliade, M., (1964), tr. Willard Trask, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, London, Arkana, p 38. ↩︎

- Lehtisalo, T., “Der Tod und die Wiedergeburt des kunftigen Schamanen”, Journal de la Societe Finno-Ougrienne, Helsinki, XLVIII, fasc. 3, 1937, pp 1-34 ↩︎

- Knight, Gareth, (2000), Dion Fortune and the Inner Light, London, Thoth, p 124. ↩︎

- Fortune, Dion, (1993), The Magical Battle of Britain, Oceanside, Sun Chalice. ↩︎

- Richardson, Alan, (1991), The Magical Life Of Dion Fortune: priestess of the 20th century, London, Aquarian, p 205.. ↩︎

@ooze well, that's pretty interesting.