While there are many causal factors contributing to the phenomenon that we call the witch hunts, I contend one way that they can be understood is in terms of a change in the conception of consciousness from group to personal dynamics. Let’s look at the many ways in which this change was evidenced in Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and why this change contributed to the bringing about of the witch hunts.

The plague was the preeminent cause of widespread and long lasting social change in Europe at that time. It was the last straw for a Western Europe that had been left staggering under the weight of the various disasters that defined the fourteenth century. With one quarter of Europe’s population dead from plague, the social changes were enormous. The plague irrevocably changed the social order, from the highest level of leadership to the family unit.

The subsequent labour shortages were a key event in the change of awareness from a group centered awareness to an individually centered one. McFarlane argues in his famous economic model1 that the manorial system was one in which consciousness was centered on the wellbeing of the group. With the collapse of this system came the beginnings of the market economy, an inherently individualistic form. One symptom of this change was that old women were being left in circumstances where they expected to be provided for by the community, but the community now didn’t want to support them. In this way the witch hunts of the period were as much a manifestation of social phenomenon as of religious fervor. You could get rid of an annoying old woman making economic demands on you by accusing her of witchcraft.

There were absolutely other causal factors apart from the economic ones. Not only did the plague cause people to examine their physical circumstances and find an individual solution the most practical, but it caused them to examine their spiritual condition as well. The god of Christianity provided no security from the plague. The priests could not even protect themselves. This only added to the longstanding dissatisfaction with the Catholic church, which the peoples of Europe were finally beginning to act on in the early sixteenth century. By this time the travesties of the schism and the decadence of the papacy generally had finally brought people to the position of truly questioning the veracity of the pope’s claim to be the one true representative of the Christian god on earth.

They were open to alternatives and Protestantism arrived to give them one. Protestantism inherently places the responsibility on the individual. I suggest that many individuals did not adapt well to the arrival of this responsibility. However, now that the focus of the community was on individual responsibilities, it became possible to blame an individual for the problems that beset that community. This presents the obvious solution that if one removes that individual the problem may be resolved.

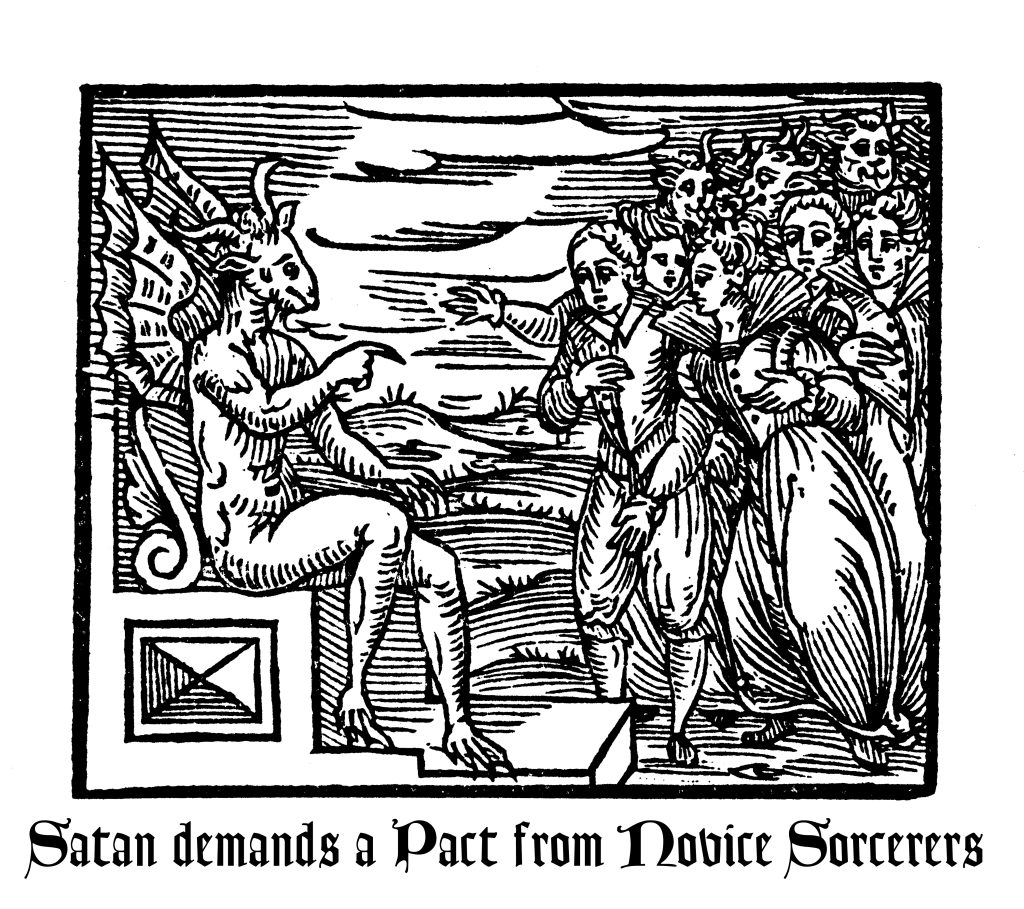

The removal of individuals in the manner of the witch hunts would not have been possible until various legal and theological changes came to pass. By the fifteenth century these changes were well on the way. The most prominent was the development of the importance of diabolic witchcraft in Christian thinking, and thus that of the law makers. The fifteenth century saw a plethora of writings on witches and their relation to demons. Among them are the commentaries on the Decretum, for example, Turrecremata’s Commentarius in Decretum Gratiani in 1445 then the Malleus Maleficarum in 14862. Turrecremata was one of the earliest writers to argue that superstitions are to be found more frequently in women than in men, a position that the Malleus went on to espouse as unquestionable fact. If you are an individual who is looking for another individual to blame for the failure of your latest endeavor, such writings were really narrowing the field as to who you should pick.

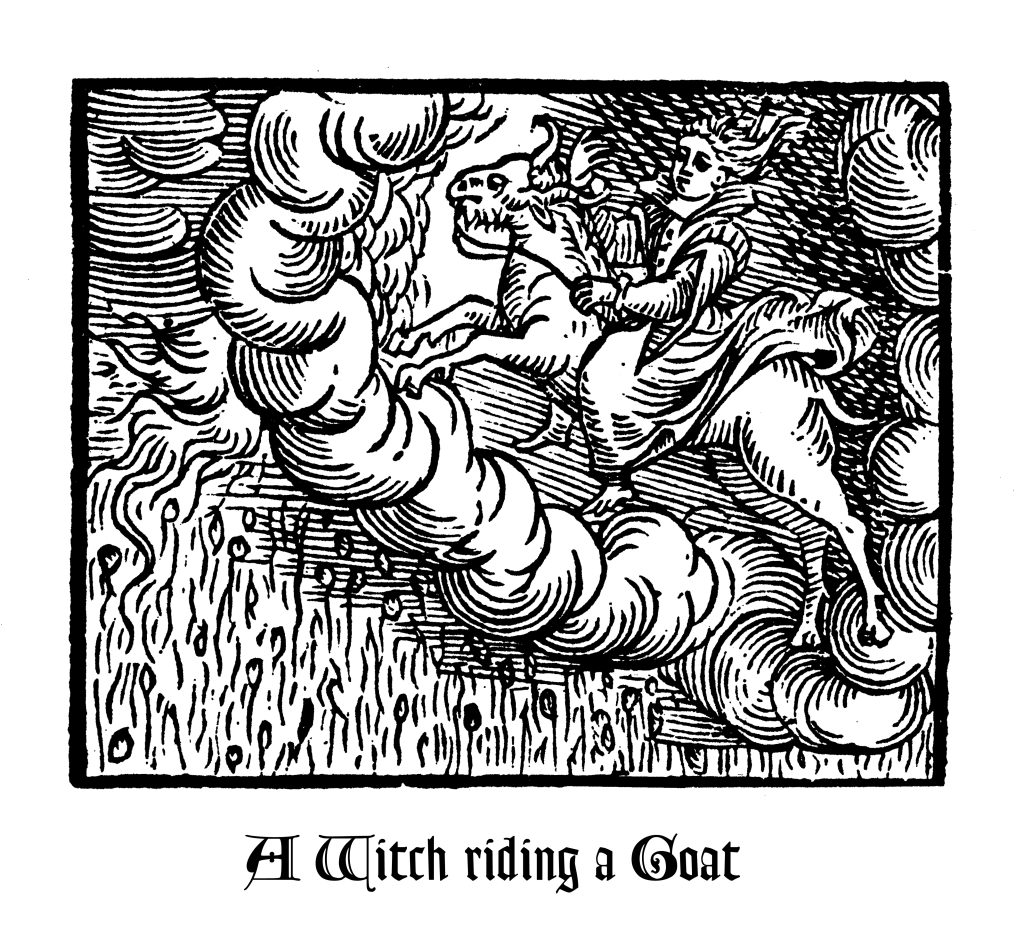

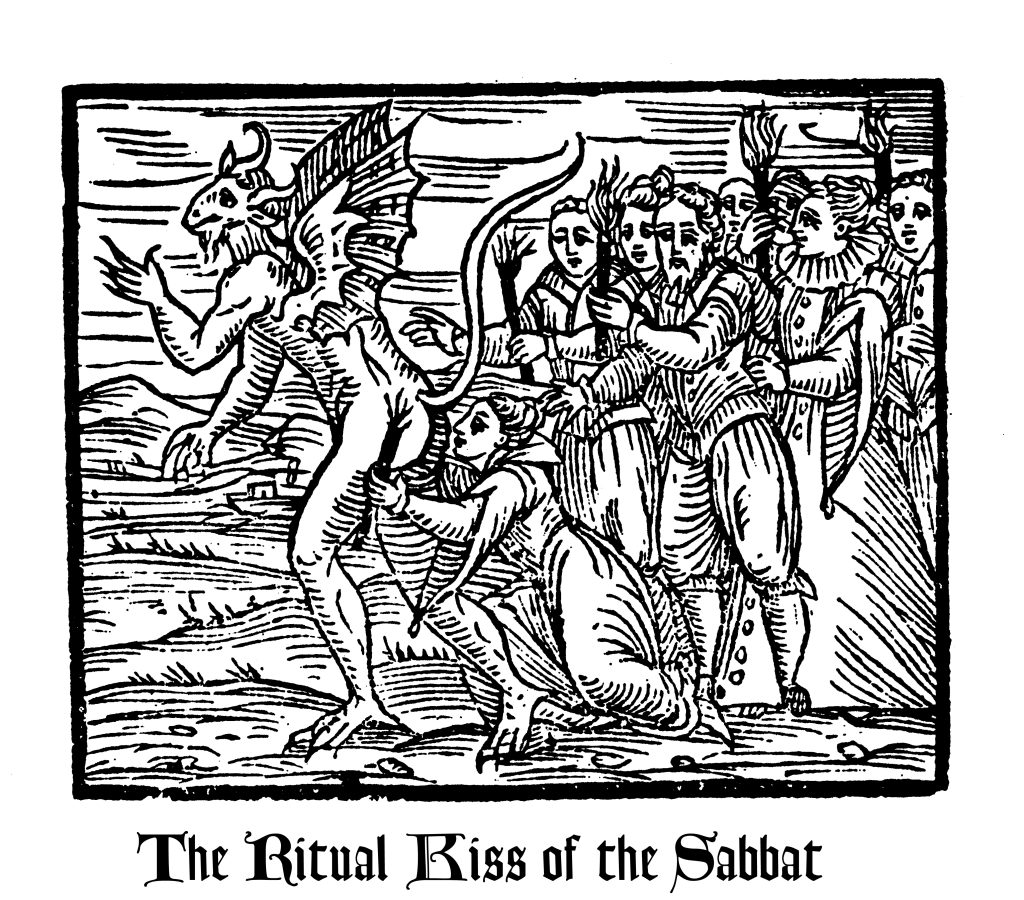

Magic was everywhere. Christianity was just as magic as witchcraft to the majority of the people. Saints’ relics were magical talismans, and if transubstantiation is not magic I don’t know what is. The Catholic church was able to convince people of the evil efficacy of witches because of this belief. They just had to invent the supposed demonic pact of witches i.e. that a witch was someone who had made a pact with the Christian devil, to show how the magic of witches was bad but the magic of the church was good. Once the Catholic church had the whole demonic pact concept explicit it was able to arrive at the position that people practicing witchcraft were not only doing harm to others, but were guilty of apostasy and heresy, and therefore subject to the most stringent strictures it was possible to impose on them. Although most early civil law which was used to prosecute witches was centered on the harm that was done, by the sixteenth century civil laws were aligned with the Christian position, firmly focused on the heretical aspects of witchcraft. Protestantism distinguished itself from the Catholic church by declaring all magic to be evil. There was no longer any possibility of there being good magic.

In the England of Henry VIII, a person who used witchcraft with the intent of causing another to love them was subject to just as harsh a penalty as one who used witchcraft to kill another3. Not only the penalty of death, but also forfeiture of lands and goods. This made witch hunting an excellently profitable enterprise. Many interesting examples of witchcraft accusations by ordinary people who were rivals in inheritance can be seen in this period, especially in the trials in the English colonies in the New World4. Once these legal structures and theological positions were in place, the way was opened for the use of an accusation of witchcraft as the means of disposing of, well anyone one might wish to dispose of really. Whether you were a king trying to get rid of an adulterous wife, or a common person jealous of a neighbour’s success, a witchcraft accusation would be just the thing to solve your problem.

In England this situation was exacerbated by the national obsession with denunciation that had been developed, by the Wars of the Roses in the fifteenth century and then by the manner in which Thomas Cromwell made religion equivalent to nationalism in the sixteenth. Along with such developing Protestant beliefs as the concept that a pious person could influence events by his petitionary prayer, these things all contributed to a world that was more and more focused on what was good for, and made possible by, the work of the individual. This was a development from the medieval position where each person had a well defined role in society and was required to fulfill the responsibilities of their position in order to ensure the stated goal, maintenance of the status quo.

The growing literacy of the population during these centuries also contributed to the growth of witch trials. There are two reasons I can ascertain for this. Firstly, if the population is literate and can get its hands on the sacred books of the day i.e. the bible, it can realise that the clergy might not be doing their job properly, in many cases because that clergy were so poorly educated that they could not read Latin or even say the mass correctly. This contributed to the growing lack of faith in the Christian religious establishment and the need to find a replacement for the protective functions that the population had previously felt the clergy fulfilled. The first printed bible appeared in 1455 and the first English bible in 1526. People could then read for themselves that “thou shalt not suffer a witch to live”5 and thus found their god commanding them to dispose of witches. This is again a switch from a group dynamic, i.e. Do what we the church tells you is in the bible, to a personal dynamic, i.e. I can see for myself that it says right here in the bible that I should get rid of all witches.

The second reason is that once you have a literate population, and the means to print and distribute information, then witch trials become media events. It was suddenly possible in the fifteenth century to effect the consistent dissemination of memes via printed, and therefore standardised books. Everyone in your town would want to get the latest gossip on “The Apprehension and confesion of three notorious Witches. Arreigned and by the Justice condemned and executed at Chelmes-forde, in the Countye of Essex, the 5. Day of July, last past. 1589.”6 Such books as this were circulated along with the black and white letter pamphlets that were in even wider circulation. In this way a pattern was built up and entered the general awareness of the minds of the people of western Europe. It had become possible for them to recognize the signs of witchcraft at work in their community. By the time of the Salem trials the participants had a detailed specification of what witchcraft was, and they enacted the specification excellently. All the world’s a stage…

The rising prosperity of the age meant that people could travel, and those who did could take books with them. Many of the Italian Humanists who were abroad in the latter part of the fifteenth century had books with them which advocated, along with the propaganda of the embryonic cult of science, the purification and renewal of Christianity. What better way to do so than to dispose of the foul enemies of their god, those in league with the devil himself.

The growth of science in this period was a collision between the primacy of faith and the growing primacy of empirical evidence and logical argument. That magic was everywhere was obvious in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, but the development of the scientific method and its promotion of the veracity of empirical facts, along with the claim that magic was not rational, was a swing from the previous position of reliance on established authorities (group consciousness) to an establishment of the importance of understanding empirical facts (individual consciousness).

The move from Catholic thinking – do what you are told to do – to Protestant thinking – read for yourself what you should do – is an exemplar of the move from groupthink to individual decision making. The realisation of this power was a spree of accusations. But this move was still nascent, and the accusers were still sufficiently under the sway of groupthink that they maintained their identification totally with the Christian polity, exercising their individual agency to label their victims as the adversaries of the Christian god.

This was religion finding expression through the weaponisation of the rational, which would ironically later morph into the rational attacking religion through the weaponisation of the religious. We all have to have faith in science now right? If nothing else the Malleus is supremely rational. The present day witch hunts of the cult of science, conducted by such authors as the ever tiresome and hypocritical Dawkins, are now of those who don’t have absolute faith in the dogma of scientism. The wheel turns.

The witch hunts were the tragic fallout of the beginning of a shift of consciousness from a group awareness to an individual awareness, perhaps one of the earliest exemplifications of the move from the age of Pisces to the age of Aquarius. Now that we are further into the Aquarian age we are seeing this tendency to individualistic expression shift to a more extreme, but quintessentially Aquarian, version of the expression of the principle of individual action. That being that the individual has not only a right to their own idiosyncratic position, but that this right includes license to viciously destroy those who do not hold that same position.

This shift was only just coming into expression in the European consciousness at the time of the witch hunts. European culture still had a long way to go until it was able to begin to release itself from the stranglehold of the groupthink of Christianity that had reigned so long there. But, I contend, this change was among the first steps on the road that lead to the primacy of scientism, including the beginnings of that most Protestant of things the cult of Capitalism, at the expense of the religious conceptions dominating Europe during the medieval period. And look how well that worked out.

- Alan MacFarlane, Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England, Oxford, 1971 ↩︎

- Edward Peters, The Magician the Witch and the Law, Pennsylvania, 1978. ↩︎

- Ewen C.H. L’Estrange, Witch Hunting and witch Trials, London, 1971, p25 ↩︎

- Carol Karlson, The Devil In The Shape Of A Woman, New York, 1987 ↩︎

- Exodus 22:18 (KJV) “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.” ↩︎

- Elizabeth Kent (ed) Witchcraft in the European Mind, Melbourne, 2001 ↩︎

Bibliography

Isaac Bonewits, Witchcraft: A concise history, (DPC Inc, 2001 e-book edition)

John Hale, The Civilization of Europe in the Renaissance, (Hammersmith, Fontana, 1993)

Carol Karlson, The Devil In The Shape Of A Woman, (New York, Norton, 1987)

Elizabeth Kent (ed) Witchcraft in the European Mind, (Melbourne, Monash University, 2001)

Gareth Knight, A History of White Magic, (London, Mowbrays, 1978)

Heinrich Kramer & James Sprenger, Malleus Maleficarum, (New York, Dover, 1971)

Ewen C.H. L’Estrange, Witch Hunting and witch Trials, ( London, Redwood Press, 1971)

Brian Levack, The Witch-hunt in Early Modern Europe, (London, Longman, 1987)

Alan MacFarlane, Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1971)

Christopher McIntosh, The Devil’s Bookshelf, (Wellingborough, Aquarian, 1985)

Margaret Murray, The God of the Witches, (London, Sampson Low, Marston & company, NDP)

Edward Peters, The Magician the Witch and the Law, (Pennsylvania, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978)

Dianne Purkiss, The Witch in the Hands of Historians, (London, Routledge, 1996)

James Sharpe, Instruments of Darkness: Witchcraft in England 1550 – 1750, (London, Hamish Hamilton, 1996)

Montague Summers, The History of Witchcraft, (New York, Barnes & Noble, 1993)

Stanley Jeyaraja Tambiah (ed), Magic, Science, Religion and the Scope of Rationality, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990)

Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic, (Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1971)

James Wasserman, The Templars and the Assassins : The Militia of Heaven, (Rochester, Destiny Books, 2001)