First I tried to make Thutmose an outfit, reasoning I could get both exactly what I wanted and a unique outfit that way. However after about ten hours of searching for documentation on how to make clothes, trying to figure out what little documentation I found, and many attempts to produce anything at all, I discovered that it was beyond me. I set it aside for the moment and decide to see what was available for sale. I was not alone. In the first community there was no one who could make clothes. In the second there was one person who could. Like good builders, these people were in high demand.

I set out to find Thutmose an outfit that was as accurate as possible to what ancient Egyptian priests actually wore. So what did they wear? Other priests in the sim told me that the ancient Egyptian priests wore all white, that they removed all body hair, didn’t wear wigs and that some priests wore leopard skins, but only if they were also warriors, and that black dye was unknown to them. My first task was to verify this information.

Most of the priests said they got their information from websites, but one or two used books. Overwhelmingly those who were priests made some sort of effort to find out what ancient Egyptians actually wore. The combatants were much less inclined to do so. Most combatants simply shopped in the world and if they found an item that said it was Egyptian, and they liked it, they bought it. Priests would swap tips with each other about good items that we had found and pass this information on to new members of the priesthood. We would visit other Egyptian themed sims to see what we could find there and then share our finds with each other. Most of those who did make the effort to do some research did not cast much of a critical eye over the quality of the websites they used as resources. If they found information on the web, it was considered valid. But most high priests made substantial effort to source accurate information.

As in all things in the world people specialized. If one could make clothes, build or script one did, and supplied others with goods. If one could do high quality research, or liked to read, one did and supplied others with information. Information was another product of the community. As in any marketplace, some products are more sought after than others. Information was not the most sought after commodity in this particular marketplace. In fact I discovered that information wasn’t considered a commodity at all. It was a thing that was outside of material consideration. If one had it one should distribute it freely to others. But to charge money for it was anathema. If one incorporated information into a product it was more highly valued. I made a hieroglyph game in the form of an obelisk and it was more valuable than just an obelisk. But no one would even consider buying the information without the object that was its form. This means that lessons are not saleable unless you make them into interactive experiences delivered via objects. To run a class and charge for it is unthinkable. One may have a donation box at lessons one gives, if the sim rules allow it, but Horemheb decreed that there should be no donation boxes in his community. Communities promoted themselves using information. They provided classes and asked for donations or had handily located shops to ensnare lesson goers.

The forums at the Egyptian Dreams1 site were recommended to me as an accurate source of information. This site had started as an online shop selling Egyptian themed objects. It subsequently developed forums, which are frequented by some Egyptologists. This site turned out to be a great source of accurate, cited, information. The Egyptologists there seemed to have infinite time to answer endless questions in great detail. The site Egyptological2, produced by amateur Egyptologists, has good quality information along with information with a more popular appeal, and was also often referred to. Another site recommended by one of my fellows was Tour Egypt3, a site belonging to a company that specialises in tours of meatspace Egypt. The information on this site is quite basic and not referenced. Blog posts, such as this post from Abagond, entitled “How Black Was Ancient Egypt?”4 were also used as sources of information. Sites that focus on Reconstructionist ancient Egyptian religion were also highly regarded. The House of Netjer5 was particularly popular as it was generally considered among my fellows that if people were practicing the same religion as the ancient Egyptians then they would be an accurate source of information. Information from all these types of site was considered equally valid. I had the advantage of being able to access a university library and it was acknowledged that the standard of information was greatly increased by my arrival. Those in the sim who could build started to come to me and ask for information to inform their builds and I’d suggest books to look for, or copy information out of books and pass it on to them.

I tried to argue that academic sites, or sites with posts by academics that provided citations, might be more reliable than, for example, blog posts. Because of this some members of the community, mostly the combatants, expressed the opinion that I was “being elitist” or making things “too hard”. On one occasion during a role play a combatant introduced herself to me and said that while her mother was both an Arab and a Muslim, her father was a Viking. When my character questioned her as to what a Muslim or a Viking were she expressed great consternation, explaining that all Medjay were Muslims and that Vikings were well known. She sent me OOC instant messages asking why I was “picking on her” and I explained that my character was justifiably unaware of both Muslims and Vikings as, seeing as our sim was set in 300 BCE, the former were not to exist for another nine hundred years and the latter for eleven hundred years. She did not receive this information with any enthusiasm but rather began an ad hominem attack on the deliverer. Overwhelmingly the priests however appreciated the quality of my input into the community.

Our community was more concerned than most with accuracy. There were other Egypts in Second Life that were much less focused on historical accuracy. One had pyramids with electric lighting, most had landscapes of nothing but sand. One had regular fireworks displays. Most didn’t have dress guidelines and were populated with Egyptians in high heels, togas and Gor clothing. Gor clothing was ubiquitous in ancient themed sims. However there was at least one Egyptian themed sim that was run by an Egyptologist and was set up with a purely educational focus. It had exceptionally accurate information and was laid out like a museum but didn’t have an associated role play community. In 2009 Rezzable6, a firm specialising in interactive experiences, held an exhibition of the treasures from Tutankhamun’s tomb in Second Life7. The quality of this build was the most detailed thing I had seen in Second Life yet. The priests visited this exhibition with great enthusiasm. This exhibition inspired me to attempt much more complex objects that I had previously built. I started to make replicas of actual objects from ancient Egypt. One example is Tutankhamun’s ecclesiastical chair (see figure 14). I spent over a week researching and then building this chair and it was well received in the community, though it couldn’t remain in the world due to the high number of prims required in its construction. Next I made a replica of a censer, then Hapsepsut’s Chapelle Rouge, and finally the entire Karnak temple complex in the time of Hapshetsut.

My natural proclivity for research had been fully engaged and, with my enthusiasm level set to high, I launched into investigating ancient Egyptian attire. I wanted to know more than just how ancient Egyptian attire looked to me, a twenty first century person of Anglo Celtic ancestry. What did their attire mean to them? Why did they choose to dress as they did? I wanted my understanding to be as real as possible. Our perceptions shape our world. An ancient Egyptian brought into our world might see designer labels as magical sigils. I wanted to try to see through Egyptian eyes.

Any assessment of the actual attire of ancient Egyptians must allow some consideration of the perceptions of the ancient Egyptians regarding colour and form. Primary among these is the fact that ancient Egypt had what we would describe as a deeply magical world view. They believed that depicting a thing as one wished it to be would cause the thing to become exactly that8. Experimentation in art was not considered a good thing, for to change the rendering of the depiction of an object or person was to risk an actual change to the thing depicted. Changes in style in Egyptian art usually came about when major changes to the society occurred, for example when a new dynasty arose, which circumstance required it to in some way differentiate itself from its predecessor9. The most extreme and the most well known example of this is the unprecedented change in style introduced by Akhenaten10. Having introduced a new theology that focused on the worship of the Aten, a solar deity, and having moved the capital of Egypt to a new location, Akhenaten was clearly distinguishing himself from all the preceding rulers of Egypt, and so it is no surprise that he should radically change the way he was represented. It was inconceivable that he should not do so, for the magical reason that a thing was not changed unless it was represented to be changed.

Because of this magical world view ancient Egyptian art depicts the world in a highly stylized manner. Usually this stylization was an antiquated one. This is especially true of attire, with people being routinely portrayed as wearing archaic forms of clothing, forms which do not correspond to actual garments found in tombs11.

The use of colour was a vital component in this proclivity for idealised representation. The word for colour, iwen, also carries the meaning of ‘nature’, ‘being’ and ‘character’12. Considering the Egyptian perception of equating cleanliness with purity, it is then hardly surprising that white was almost invariably the colour used to depict clothing, particularly for priests13. This is however a case where the depiction actually matched the reality, for most Egyptian clothing was in fact white, or off white14.

I eventually found that most of the information my fellow priests had given was quite correct, though some was bogus. It turns out priests of ancient Egypt did, on the whole, wear plain white linen clothing15, remove their body hair16, and it also seems that the nearest colour to black that the ancient Egyptians had access to was indigo blue17. Some priests did also wear leopard skins18, though the wearing of same had nothing to do with being a warrior.

Most priests wore the same basic white linen garment as they had through the whole of Egyptian history19 and white palm sandals20 and would only have been recognizably different from non priests by the “archaic sobriety of their garb”21. It was only specialists, or those of high rank who had a distinctive item of clothing to mark them out from their fellows22. The plain white garment of priests seems to have had had some variety of form.

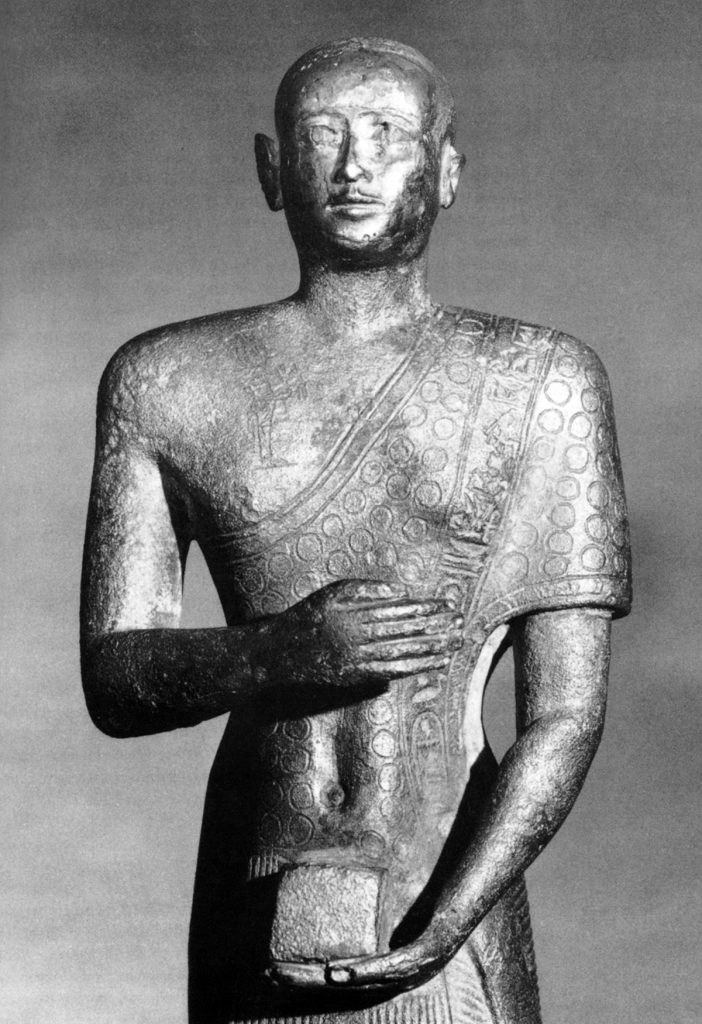

The lowest levels of priests would be indistinguishable from non priests in their wearing of a simple white kilt (see figure 15)23. However even slightly higher ranking priests seem to have favored a more archaic form of kilt (see figure 16), that came from chest to mid calf and with a diagonal strap24. Ancient Egypt was a land where antiquity was highly regarded25 and so this garment had status on account of its being archaic. This is reflected in the fact that it was the official dress of the vizier of Thebes in the New Kingdom26.

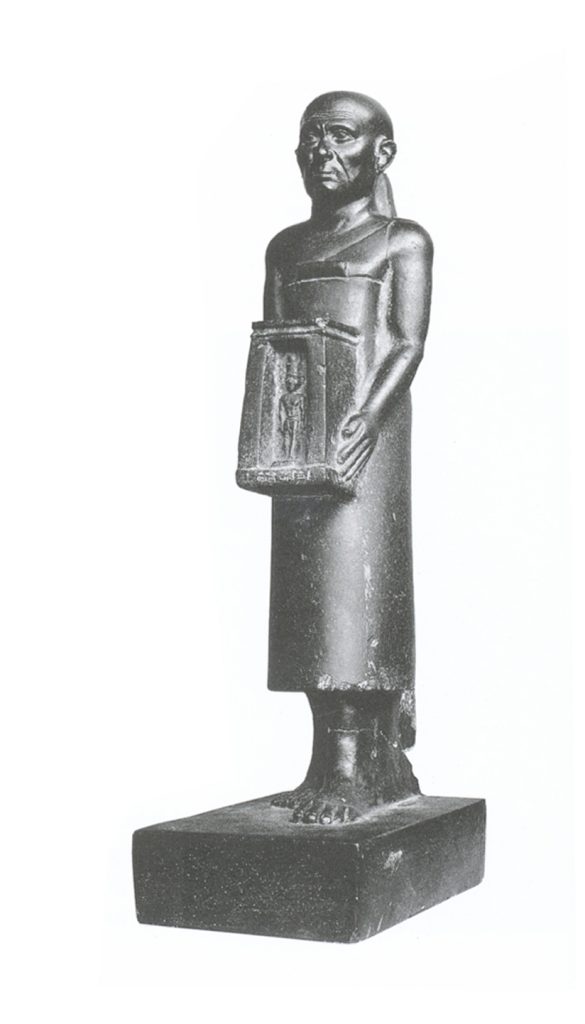

While priests were required to remove all their body hair they also however clearly wore the ubiquitous wigs (see figure 19)27. This stela of Montemhet, fourth prophet of Amun (hm netjer fed-nu en Amun)28 the fourth highest ranking priest at Karnak29 clearly shows him wearing a wig. But this is where things get interesting as the concept of a priest in ancient Egypt is quite different from the one we have today. In ancient Egypt most priests worked for the temple part time30, on a rotating basis31. The rest of the time they lived in the villages, married and had children and held other occupational roles32. So, although the image shows Montemhet wearing a wig it doesn’t necessarily mean he would wear one when actually undertaking his temple duties.

The meaning of the word for the most basic category of priest, wab is ‘pure one’33 34. While this included a moral understanding of pure, the main aspect of purity was cleanliness35. For an ancient Egyptian, cleanliness was definitely next to godliness. Before a priest attended to their duties in the temple they would be required to attend the sacred lake where they would wash and shave their bodies and wash their mouths out with natron36. It was this ritual action which marked the symbolic transition from ordinary person to priest37. This made me think that perhaps priests wore wigs normally and then removed them before commencing their sacerdotal bathing.

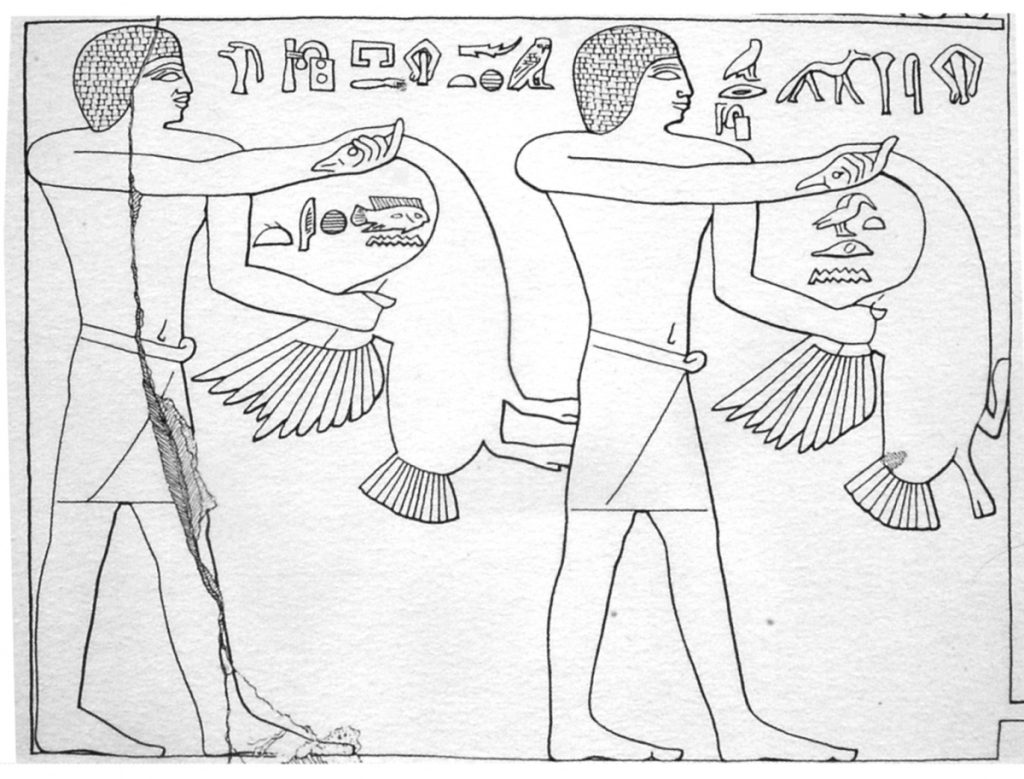

Further searching revealed an image of a sem priest (see figure 20)38, who is wearing a wig while performing his duties. We know he is doing so as in the center left of the image we can see he is holding a censer with a head of a falcon, like the one in figure 1739. This seems to indicate that while priests were required to remove all their body hair they still wore wigs, even when performing their temple duties. However I remained confused as many images of priests show them clearly clean shaven. Just to confuse things further, priestess were invariably shown wearing wigs.

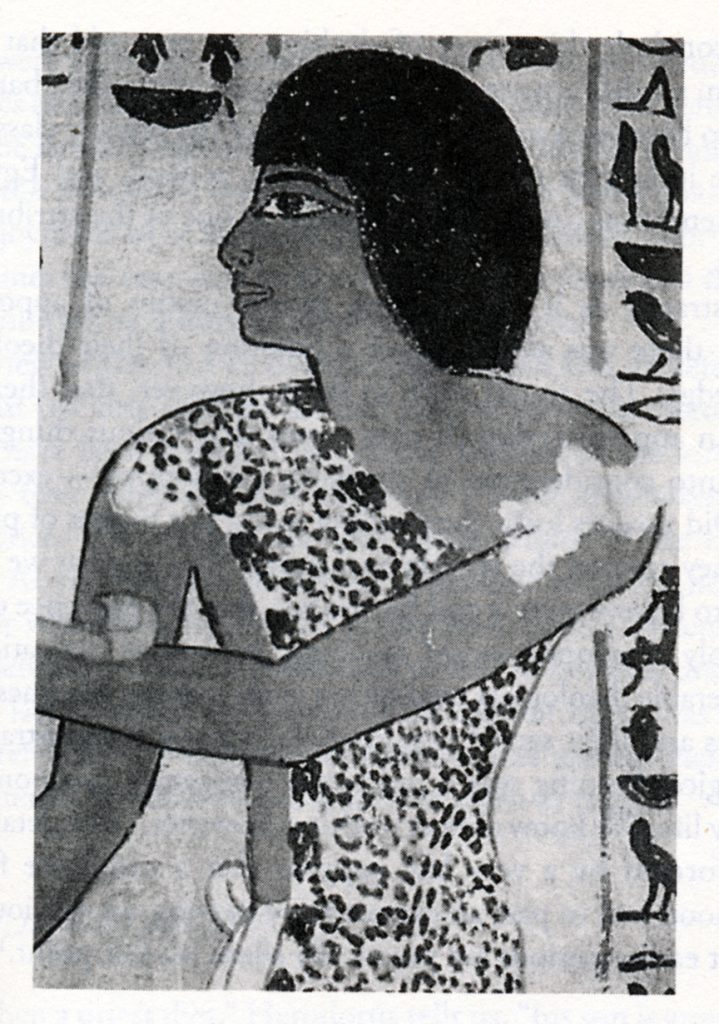

A leopard skin garment was worn by sem priests40 41 42, for instance figure 1843 shows Khonirdis, a high official and priest of the seventh century BCE wearing a leopard skin. The sem priest was a quite prestigious position, as evidenced by the fact that Khemwaset, a son of Ramses II, put his priestly title of sem before his title of king’s son44. However the wearing of this particular garment had nothing to do with being a warrior, but rather seems to have been a relic of an earlier time when priests had a more shamanistic role45. In this respect the leopard skin was considered a badge of office.

Sem priest

I was only a humble hem netjer, so I went off in search of a plain white outfit for Thutmose. It was to be much more difficult a task than I thought. Mostly people come to Second Life to live a fantasy. They want it to be fun. Because, unlike in most games, in the world one can build anything, within the technical limitations of the client, people do. They give their imaginations free reign and create things that are fun and pretty. But pretty is a very subjective thing, and the range of facility users have with the building tools varies widely, thus results vary. Moreover in the world there can be a profit motive. People can sell their creations for Linden dollars that can be exchanged for meatspace currencies. Some residents build for the fun of it. Some for the profit and all shades of grey in between. Authenticity does not necessarily sell better than a more imaginative approach, and it was the latter that prevailed.

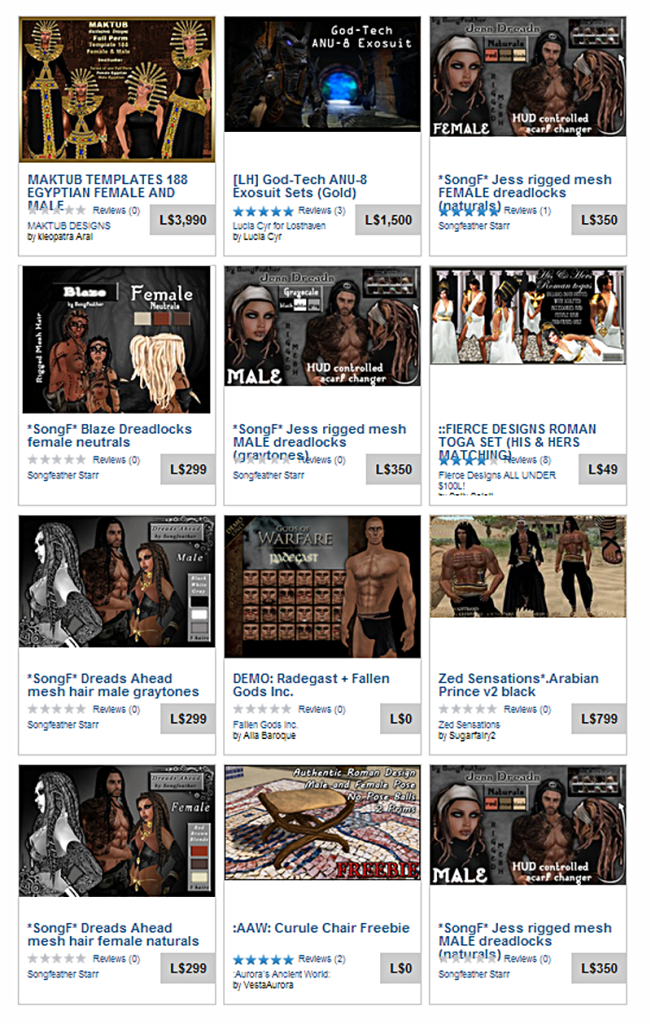

Being by this time familiar with the awfulness of the inworld search, I began my search for clothing on the Second Life web shop Xstreet. Its search was not much better than the inworld search. The results of a search for Egyptian male items are shown in figure 21. Of the twelve items shown on this the first page of the search listing, only three seem to have any connection with anything Egyptian. The first one, while definitely Egyptian in theme, is clearly female clothing. The second is a scary looking Anubis like suit and the ninth is an outfit for an Arabian prince. That this is the result of a failure in the search system is demonstrated by the presence of actual Egyptian themed, male clothing that I was able to find, after much browsing though many, many pages. However this process was still less time consuming than traipsing around many, many sims in the world.

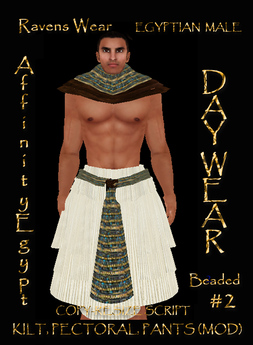

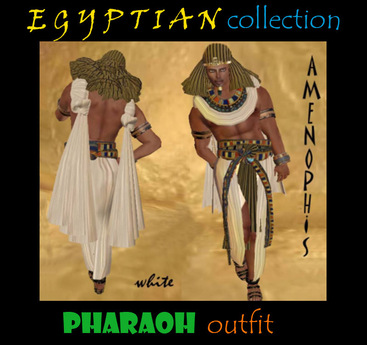

The closest matches to my imagined perfect priest outfit can be seen in figures 22 to 26. I was not immediately struck by the authenticity or attractiveness of any of them. None of them advertise that they specifically set out to depict priestly attire. While all of the outfits contain at least one item of clothing that is completely unlike anything we know of that was worn by ancient Egyptians, they do each include some aspects of ancient Egyptian attire. They also include some attempts at constructing items worn by ancient Egyptians which failed to live up to the reality, perhaps on account of the difficulty of replicating the genuine object due to the limitations of the Second Life building tools. For instance all but one of them, with greater and lesser degrees of success, attempt some variant of the Egyptian collar the usekh46. This item is very tricky to replicate in the world as one cannot construct a flexible disc shape. Perhaps this is why figures 22, 24 and 26 contain articles worn on the shoulder and/or chest that bear so little resemblance to any known items of ancient Egyptian attire. Perhaps the creator was allowing their imagination free reign, or perhaps some combination of these two reasons.

Three of the five (figures 24, 25 & 26) depict attempts at the nemes head covering, also a difficult item to construct with the Second Life building tools. All of these outfits attempt a version of the ubiquitous kilt, though most depict it as much longer than usually worn by most ancient Egyptians. Although all the outfits shown here are in white most of them were available in a range of colours. In fact white was the least popular colour offered. I deduce this from the example of the Akhu outfit (figure 24), which was also offered in black but had just 3 reviews for the white version and 26 for the black. Moreover outfits in white did not predominate: a vast array of extremely bright colours did. This propensity is clearly demonstrated in figure 27 which shows the full range of Egyptian outfits from a single merchant.

Kahn el Khalili range

Despite most ancient Egyptian clothing being white in colour47 only one of these outfits is available in white. Generally the outfits conform more to a stereotyped Disney vision of ancient Egypt than the reality.

Priests tended more towards authentic outfits but most others in the community were much less inclined towards such outfits. I decided to go for the most accurate outfit I could find. Eschewing the bright colours that characterized most male outfits in the community, I chose a plain white kilt, no wig and, most atypically of all, no weapons. The closest I could get to a plain white, short, kilt was the kilt from the Akhu outfit, which included a coloured belt. When one buys an outfit one can wear selected components of that outfit. For example I was able to refrain from wearing the poorly rendered, brightly coloured nemes which came with Akhu, as well as the brightly coloured chest covering. However the kilt came with the brightly coloured belt attached. Because the vendor of this outfit had chosen to apply restrictive no modify permissions settings I was unable to modify the kilt to either remove the belt or change its colour. I resigned myself to my fate and adopted it as my new look. Being totally unable to find any footwear resembling Egyptian sandals (most people in the community wore Roman sandals as that was all that was available) I decided to go barefoot.

With his new high quality skin and minimalist priestly outfit Thutmose looked good (see figure 28). He also looked real. I attribute this to two things. Firstly, his lack of perfection. Most avatars were idealized representations. They looked as if their humans had set out to make the youngest, most buff, handsome, happiest avatar people in the world, avatars that looked as much as possible like how the person really wanted their meatspace selves to look. In their defense, it is hard to produce an avatar in Second Life that looks old, or worn. The vast majority of avatar skins available are young and fresh and perfect. Secondly I was looking at him a lot. At this time I was spending about a hundred hours a week in the world. Admittedly I spent most of the time looking at the back of his head, as my preferred view when walking around in the world was a view that put my perspective slightly above and behind Thutmose’s head.

The avatar customisation tools do allow one a fair range of latitude in customising the avatar’s face, but this is limited to changing the proportions and size of parts of the face. It is the skin that gives the avatar an age specific look. The new skin made him look much older than all the other avatars in the community. I had expended some effort to make Thutmose look grumpy, as this was a trait I wanted to express in the character. Despite this I found I liked him. Grumpy looking and scarred as he was, I felt fondly toward him. He was starting to feel like a part of me. I started to notice that these new alterations made others treat him differently too. People started spontaneously addressing him as “wise one” and most of the priestesses suddenly deferred to him, even though his rank had not changed.

Initially Thutmose had walked like a noob, with the stilted gait of the default walking animation. So I had obtained an animation override (AO) for him. Some AOs are just sets of basic animations created using Poser, or similar software, but the better ones are made by making motion captures of meatspace humans and converting these into animations. This meant Thutmose now had his own distinctive walking, standing and sitting motions. That he no longer walked with the crude, stiff noob walk made an appreciable difference to his reality status. Without input from me he would shift his position, or scuff his feet as if bored. He was starting to have a life of his own. This life was also starting to affect his status in the community. Those who didn’t have AOs for their avatars were socially disadvantaged and one would hate to meet another person using the same AO. It was a social faux pas on the same level as meeting someone wearing the exact same outfit.

I realized that the ancient Egyptians had a point, I had made an image and that action had brought a thing into being. In this case the appearance was the entire thing as Thutmose had no other being than his avatar. Or did he? Thutmose is not me, but neither is he not of me. Some parts of him are me, parts of both the backstage and front stage me. He is also things other than me. He is the self of the actions I tell him to do that performs itself back at me, plus the self that is performed from things that do not come from me. Not only the noise in the system, but his AO for example. It is a set of bodily movements that are not in any way derived from those of my meatspace body. They are movements created by making a motion capture of the movements of another person entirely. But they are being performed at me via the medium of a self I see as part of myself, while also having parts that do not overlap my self. The noise in the system sometimes makes the avatar do quite discrete things. Sometimes, due to glitches in the communication with the server, he would walk off, completely out of my control. All I could do was wait until the system established correct communications with my client again. In these times it was as if he took on a life of his own and I was forced to realise that he was not my willing minion. In this way Thutmose has parts of his self that are entirely not me: the noise in the system plus such things as his AO. I chose these animations for him but they, and the system noise, came from completely outside of my self.

But was the thing I had brought into life a fiction? Perhaps less a fiction than the character with a Muslim mother and Viking father in 300 BCE. But still a not entirely accurate representation of an ancient Egyptian man. Thutmose’s skin was caucasian for a start. Much research has been done into what the skin colour of ancient Egyptians was like and while there is still a lack of consensus as to the exact tones of their skin it is highly unlikely that ancient Egyptians were white48. I had selected Thutmose’s skin for its realism, but it almost certainly isn’t any kind of reasonable representation of an accurate ancient Egyptian skin tone. In my defense, high quality darker skins were not available. The maker of Thutmose’s skin made an Asian skin, but not any darker toned skins. There were some darker skins available in the world, but I had chosen a skin of a lighter tone than I reasonably believed was representative of ancient Egyptian skin colours because I preferred a higher quality skin over a more accurately coloured one. My nascent connection to Thutmose drove me to make him look as much like a real human as possible. I had chosen one kind of reality over another. But I had done this for the very practical reason that it was not possible to have both at once.

- Egyptian Dreams, Ancient Egyptian Discussion Board, http://forum.egyptiandreams.co.uk/, Accessed 09/02/2014. ↩︎

- Byrnes, A., Phizackerley, K., Egyptological: Your free online Ancient Egypt Magazine, http://www.egyptological.com/, Accessed 09/02/2014. ↩︎

- Tour Egypt, Tour Egypt, http://www.touregypt.net/, Accessed 09/02/2014. ↩︎

- Abagond, (2009), How Black Was Ancient Egypt?, http://abagond.wordpress.com/2009/12/21/how-black-was-ancient-egypt/, Accessed 09/02/2014. ↩︎

- The House of Netjer, The Kemetic Orthodox Faith, http://www.kemet.org/, Accessed 09/02/2014. ↩︎

- Rezzable, Rezzable, http://rezzable.com/, Accessed 09/02/2014. ↩︎

- Rezzable, King Tut, http://rezzable.com/rezzable-experience/king-tut, Accessed 09/02/2014. ↩︎

- Wilkinson, R. H., (1999), Symbol & Magic in Egyptian Art, Thames and Hudson, New York, p. 7. ↩︎

- Wilkinson, R. H., (1999), Symbol & Magic in Egyptian Art, Thames and Hudson, New York, p. 13. ↩︎

- Wilkinson, R. H., (1999), Symbol & Magic in Egyptian Art, Thames and Hudson, New York, p. 51. ↩︎

- Redford, D. B. (ed), (2001), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, New York, Vol. 1, p. 274. ↩︎

- Wilkinson, R. H., (1999), Symbol & Magic in Egyptian Art, Thames and Hudson, New York, p. 104. ↩︎

- Wilkinson, R. H., (1999), Symbol & Magic in Egyptian Art, Thames and Hudson, New York, p. 109. ↩︎

- Redford, D. B. (ed), (2001), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, New York, Vol. 1, p. 278. ↩︎

- Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 40. ↩︎

- Gee, J. L., (1998), The Requirements of Ritual Purity in Ancient Egypt, Ph. D. Dissertation (Unpublished), Yale University, New Haven. ↩︎

- Redford, D. B. (ed), (2001), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, New York, Vol. 3, p. 491. ↩︎

- Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 41. ↩︎

- Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 40. ↩︎

- Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 42. ↩︎

- Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 41. ↩︎

- Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 41. ↩︎

- Teeter, E., (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, New York, p. 23. ↩︎

- Wilkinson, R. H., (2000), The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt, Thames and Hudson, New York, p. 91. ↩︎

- Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 41. ↩︎

- Redford, D. B. (ed), (2001), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, New York, Vol. 1, p. 276. ↩︎

- Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 7. ↩︎

- Lichtheim, M., (1980), Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume III: The Late Period, University of California Press, Berkeley, p. 30. ↩︎

- Dodson, A., Hilton, D., (2004), The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames and Hudson, New York. ↩︎

- Wilkinson, R. H., (2000), The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt, Thames and Hudson, New York, p. 91. ↩︎

- Teeter, E., (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, New York, p. 18. ↩︎

- Teeter, E., (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, New York, p. 17. ↩︎

- Teeter, E., (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, New York, p. 27. ↩︎

- Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 36. ↩︎

- Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 36. ↩︎

- *Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 36. ↩︎

- Teeter, E., (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, New York, p. 18. ↩︎

- Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 41. ↩︎

- From http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ancient_Egyptian_censer.jpg ↩︎

- Teeter, E., (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, New York, p. 24. ↩︎

- Sauneron, S., (2000), The Priests of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, New York, p. 41. ↩︎

- Morgan, M., (2008), Supernatural Assault in Ancient Egypt: Seth, Renpet & Moon Magick, Mandrake of Oxford, Oxford, p. 18. ↩︎

- Pinch, G., (1994), Magic in Ancient Egypt, British Museum Press, London, p. 71. ↩︎

- Teeter, E., (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, New York, p. 25. ↩︎

- Helck, W., (1984), “Schamane und Zauberer”, in Gutbub, A., Mélanges Adolphe Gutbub, Institut d’Égyptologie, Montpellier, pp. 103-108. ↩︎

- Wilkinson, A., (1971) Ancient Egyptian jewellery, Methuen, London, p. 31. ↩︎

- Redford, D. B. (ed), (2001), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, New York, Vol. 1, p. 278. ↩︎

- Redford, D. B. (ed), (2001), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, New York, Vol. 1, pp. 293-294. ↩︎